Heaven forbids, I should neglect to mention that San Pedro de Atacama–given its high altitude, and being as dry and remote as it is–also has the darkest sky on the planet, making it ideal for stargazing. And astronomers from across the globe are betting that ALMA’s array of 66 dishes–comprising the world’s largest ground-based telescope–can provide answers about our cosmic origins and our search for life within and beyond our universe.

Already, the ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) Observatory has made many significant discoveries, including:

- In 2018, astronomers detected the presence of the most distant oxygen molecules ever observed, located a staggering 13.28 billion light-years away. This remarkable finding significantly contributed to our understanding of cosmic evolution, shedding light on the emergence of star formation in this distant galaxy a mere 250 million years after the Big Bang.

- Additionally, ALMA made a stunning revelation by identifying billions of tons of table salt in orbit around a young star, offering a mesmerizing glimpse into the presence of familiar compounds in the cosmos.

- Furthermore, ALMA has played a pivotal role in unraveling the mysteries of the universe. For instance, it detected branched organic molecules in a star-forming region of our Milky Way, providing valuable insights into the chemical composition of celestial bodies.

- Moreover, ALMA’s observations have extended to other galaxies, such as the groundbreaking discovery of a disc around a star in a distant galaxy–a first-of-its-kind observation that advanced our understanding of stellar systems beyond our own. Furthermore, by studying a newly dormant galaxy, ALMA uncovered evidence of significant celestial events, identifying the ejection of star-forming fuel during a galactic merger and the formation of gas-rich tidal tails, providing a window into the cosmic processes that shape our universe.

- ALMA has also helped researchers determine the types and locations of systems that could support habitable planets. ALMA has also provided information about worlds closer to home, including Saturn’s moon Titan.

Sadly, there was no time in our itinerary to visit the ALMA facility, which welcomes all visitors during Saturday and Sunday. However, I attempted some astrophotography discoveries of my own during a celestial presentation at the edge of our resort, Hotel Cumbres San Pedro de Atacama, in my hope of capturing a vivid photograph of the night sky.

Armed with my Sony RX10 iv and tripod, our expedition troop marched in total darkness to the final plank of the resort’s boardwalk, bringing us to open desert, where two mounted telescopes were pointed at a black sky illuminated by a million points of light. The view was breathtaking! While most of the guests stretched out on pillows and blankets, I set up a camp chair and set my coordinates.

Regrettably, I failed. In order to reduce the digital noise during a long exposure, I adjusted the ISO to 400, which gave me a 30-sec. time exposure with an open aperture. The result was a tangle of small streaks, not stars. Apparently, the long exposure captured the path of the moving sky, albeit 3 shooting stars were framed in the effort.

Unwilling to admit defeat–the night before our return to Santiago–I leveled the tripod within the confines of my private garden and turned my camera toward the sky with newfound hope and a higher ISO to reduce my exposure. This time, the results were more satisfying.

While I had hoped for a glimpse of the Milky Way, I’ll settle for a Mars Bar from Valle de la Luna!

Next up: South America capitals…

as the roar of the Gunnison River echoes against the sheer walls of gneiss and schist.

as the roar of the Gunnison River echoes against the sheer walls of gneiss and schist.

The river’s pivotal role in carving out 2 million years of metamorphic rock has resulted in canyon walls that plunge 2700 vertigo-inducing feet at Warner Point into wild water that has been rated between Class V and unnavigable.

The river’s pivotal role in carving out 2 million years of metamorphic rock has resulted in canyon walls that plunge 2700 vertigo-inducing feet at Warner Point into wild water that has been rated between Class V and unnavigable.

The view at Dragon Point showcases brilliant stripes of pink and white quartz extruded into the rock face, personifying two dragons who have symbolically fused color into a somber Precambrian edifice.

The view at Dragon Point showcases brilliant stripes of pink and white quartz extruded into the rock face, personifying two dragons who have symbolically fused color into a somber Precambrian edifice.

and focuses on an untamed water system that’s required three dams to slow the erosion of the canyon floor.

and focuses on an untamed water system that’s required three dams to slow the erosion of the canyon floor. According to Park Service statistics, left unchecked, the Gunnison River at flood stage would charge through the gorge at 12,000 cubic feet per second with 2.75 million-horse power force. Dams now provide hydroelectric energy, and have created local recreation facilities for water sports, including Blue Mesa Reservoir, Colorado’s largest body of water.

According to Park Service statistics, left unchecked, the Gunnison River at flood stage would charge through the gorge at 12,000 cubic feet per second with 2.75 million-horse power force. Dams now provide hydroelectric energy, and have created local recreation facilities for water sports, including Blue Mesa Reservoir, Colorado’s largest body of water.

The trail ends at a sandbar where eager Mexicans negotiate with Gringos to ferry them across the river by rowboat. Five dollars is generally the agreed upon price.

The trail ends at a sandbar where eager Mexicans negotiate with Gringos to ferry them across the river by rowboat. Five dollars is generally the agreed upon price. However, with the Rio Grande water levels so low, Leah and I found it cheaper to wade across fifty feet of knee-deep water to the other side.

However, with the Rio Grande water levels so low, Leah and I found it cheaper to wade across fifty feet of knee-deep water to the other side. Land transportation comes from Uber burros, charging five dollar fares to cover the dusty and shit-laden ¾-mile trip…

Land transportation comes from Uber burros, charging five dollar fares to cover the dusty and shit-laden ¾-mile trip… …to a white trailer check-point surrounded by cyclone fencing on the edge of the village. It was a treat to sit in Boquillas’s only air conditioning for a few minutes to escape the 100◦ heat, while our identities were checked against a drug cartel database.

…to a white trailer check-point surrounded by cyclone fencing on the edge of the village. It was a treat to sit in Boquillas’s only air conditioning for a few minutes to escape the 100◦ heat, while our identities were checked against a drug cartel database. …with an overlook of the Boquillas Canyon.

…with an overlook of the Boquillas Canyon. Mama Falcone was sitting on the patio in her kitchen apron working on a future needlepoint tapestry that would soon display in the family curio shop next door, while her nephew Renaldo brought us menus and took our order—chicken quesadilla for Leah, and beef burrito for me. Meanwhile, a family of three from South Carolina sat at a nearby table chatting it up with Mama’s daughter, Lillia.

Mama Falcone was sitting on the patio in her kitchen apron working on a future needlepoint tapestry that would soon display in the family curio shop next door, while her nephew Renaldo brought us menus and took our order—chicken quesadilla for Leah, and beef burrito for me. Meanwhile, a family of three from South Carolina sat at a nearby table chatting it up with Mama’s daughter, Lillia. The town population shrank from three hundred to one hundred adults and children, with many leaving for Muzquiz—the nearest Mexican city, and a seven-hour bus ride away. Eventually, Mama and Lillia found work in the States, but returned home to the restaurant after the crossing officially reopened in April 2013.

The town population shrank from three hundred to one hundred adults and children, with many leaving for Muzquiz—the nearest Mexican city, and a seven-hour bus ride away. Eventually, Mama and Lillia found work in the States, but returned home to the restaurant after the crossing officially reopened in April 2013. They are hopeful for an economic recovery, but the town is in shambles, and it will take many more Americans to salvage Boquillas’s economy.

They are hopeful for an economic recovery, but the town is in shambles, and it will take many more Americans to salvage Boquillas’s economy.

I have met the enemy face to face and I do not fear them. Their rowboats and mules would be no match against our ships and tanks.

I have met the enemy face to face and I do not fear them. Their rowboats and mules would be no match against our ships and tanks.

Earlier in the day, border patrol had sped past our campsite from the southern border, causing us to speculate whether an ICE officer had just interdicted an illegal border crosser. And so, with the sun at our backs, and our batteries recharged, I fired up the F-150, turned right on Texas FM (farm-to-market road) 2627, and headed due south in search of bad hombres. The radio god immediately synchronized his playlist with our mission, and delivered David Byrne belting out the lyrics to “We’re on the Road to Nowhere”.

Earlier in the day, border patrol had sped past our campsite from the southern border, causing us to speculate whether an ICE officer had just interdicted an illegal border crosser. And so, with the sun at our backs, and our batteries recharged, I fired up the F-150, turned right on Texas FM (farm-to-market road) 2627, and headed due south in search of bad hombres. The radio god immediately synchronized his playlist with our mission, and delivered David Byrne belting out the lyrics to “We’re on the Road to Nowhere”. Historically, the bridge was constructed by Dow Chemical in 1964 to transport fluorite from Coahuilan mines across Heath Canyon to America. But U.S. and Mexican authorities shuttered the bridge in 1997, suspecting drug smuggling. Other reports cite the murder of a Mexican customs official as the reason behind the bridge closure.

Historically, the bridge was constructed by Dow Chemical in 1964 to transport fluorite from Coahuilan mines across Heath Canyon to America. But U.S. and Mexican authorities shuttered the bridge in 1997, suspecting drug smuggling. Other reports cite the murder of a Mexican customs official as the reason behind the bridge closure. Across the border stand the remnants of a faded factory.

Across the border stand the remnants of a faded factory. Broken buildings and slanted warehouses survive in silence against a brown mountain backdrop.

Broken buildings and slanted warehouses survive in silence against a brown mountain backdrop. Yet in the distance to the right of the river, La Linda mission stands alone—its double towers dwarfed by nature’s majesty, and its church doors removed for a purpose higher than God.

Yet in the distance to the right of the river, La Linda mission stands alone—its double towers dwarfed by nature’s majesty, and its church doors removed for a purpose higher than God. There are those who would welcome a return to the border crossing.

There are those who would welcome a return to the border crossing. Committee meetings and feasibility studies on both sides of the river argue the benefits of potential tourism and ease of crossing without traveling to either Del Rio or Presidio. Currently, a legal crossing to La Linda would take nearly 10 hours by car versus 10 minutes by illegal foot path. But there are no travelers today, or at any other times. It’s just too remote.

Committee meetings and feasibility studies on both sides of the river argue the benefits of potential tourism and ease of crossing without traveling to either Del Rio or Presidio. Currently, a legal crossing to La Linda would take nearly 10 hours by car versus 10 minutes by illegal foot path. But there are no travelers today, or at any other times. It’s just too remote.

and into the twilight, fluttering en masse, up and over the trees.

and into the twilight, fluttering en masse, up and over the trees. A continuous and frenzied swarm pours from the cave in a procession that could last up to two hours.

A continuous and frenzied swarm pours from the cave in a procession that could last up to two hours. With the exception of some rogue bats that fly off in scattered directions, the mother lode hooks right and follows a path 50 miles due east to Uvalde in search of mosquitoes and corn earworms, a tasty moth that wreaks havoc on a number of Southern crops.

With the exception of some rogue bats that fly off in scattered directions, the mother lode hooks right and follows a path 50 miles due east to Uvalde in search of mosquitoes and corn earworms, a tasty moth that wreaks havoc on a number of Southern crops. Historically, the Sergeant family, who farmed this property from the early 1900’s, protected the cave entrance with fencing in order to mine the accumulated guano, which provided important income to the ranchers until 1957 when sold as premium fertilizer and an explosive constituent.

Historically, the Sergeant family, who farmed this property from the early 1900’s, protected the cave entrance with fencing in order to mine the accumulated guano, which provided important income to the ranchers until 1957 when sold as premium fertilizer and an explosive constituent. Having over-nighted for three days in the park, I can testify that there is no shortage of annoying bugs here. Not to be selfish, but I’d like to propose that some of the bats stay behind and clean up inside the park’s perimeter. If the bats only knew that they could dine closer to home–forsaking the 100-mile round-trip–then I could better enjoy my outdoor dinner plans as well.

Having over-nighted for three days in the park, I can testify that there is no shortage of annoying bugs here. Not to be selfish, but I’d like to propose that some of the bats stay behind and clean up inside the park’s perimeter. If the bats only knew that they could dine closer to home–forsaking the 100-mile round-trip–then I could better enjoy my outdoor dinner plans as well.

or find a blanket-sized parcel of grass to relax and watch the sun go down;

or find a blanket-sized parcel of grass to relax and watch the sun go down; or pull up in a boat to wait for showtime.

or pull up in a boat to wait for showtime. One fellow standing behind me seems to be mystified by the whole experience. “Are they gonna fly outta that sewer hole over there?” he wonders out loud.

One fellow standing behind me seems to be mystified by the whole experience. “Are they gonna fly outta that sewer hole over there?” he wonders out loud. His misconception is immediately corrected by a 10-year old standing nearby. “Hey mister, this isn’t Batman, y’know! They come out from under the bridge where they live,” says Einstein boy.

His misconception is immediately corrected by a 10-year old standing nearby. “Hey mister, this isn’t Batman, y’know! They come out from under the bridge where they live,” says Einstein boy. I too am excited to catch the bats in flight, but I’m also interested in doing something different with my Lumix, which I’m still learning to use. I’m determined to capture the bats in motion!

I too am excited to catch the bats in flight, but I’m also interested in doing something different with my Lumix, which I’m still learning to use. I’m determined to capture the bats in motion! The moment arrives when the first bats emerge, and the crowd gets giddy.

The moment arrives when the first bats emerge, and the crowd gets giddy. And moments later, the floodgates open, and the bats streak across the night sky by the thousands–

And moments later, the floodgates open, and the bats streak across the night sky by the thousands– a migration wave of epic proportions that approaches a feeding frenzy.

a migration wave of epic proportions that approaches a feeding frenzy. I confess that the photos are experimental. However, I understand that there are traditionalists who need to see things as they are, versus my interpretation of the event. So, in fairness to those whose vision is less oblique than mine, I’ve increased the camera’s shutter speed to give a more accurate representation of the bats’ flight path…

I confess that the photos are experimental. However, I understand that there are traditionalists who need to see things as they are, versus my interpretation of the event. So, in fairness to those whose vision is less oblique than mine, I’ve increased the camera’s shutter speed to give a more accurate representation of the bats’ flight path… such that even Meat Loaf would be impressed.

such that even Meat Loaf would be impressed.

The other condition is a more common affliction commonly known as drifting-into-ditch-itis.

The other condition is a more common affliction commonly known as drifting-into-ditch-itis.

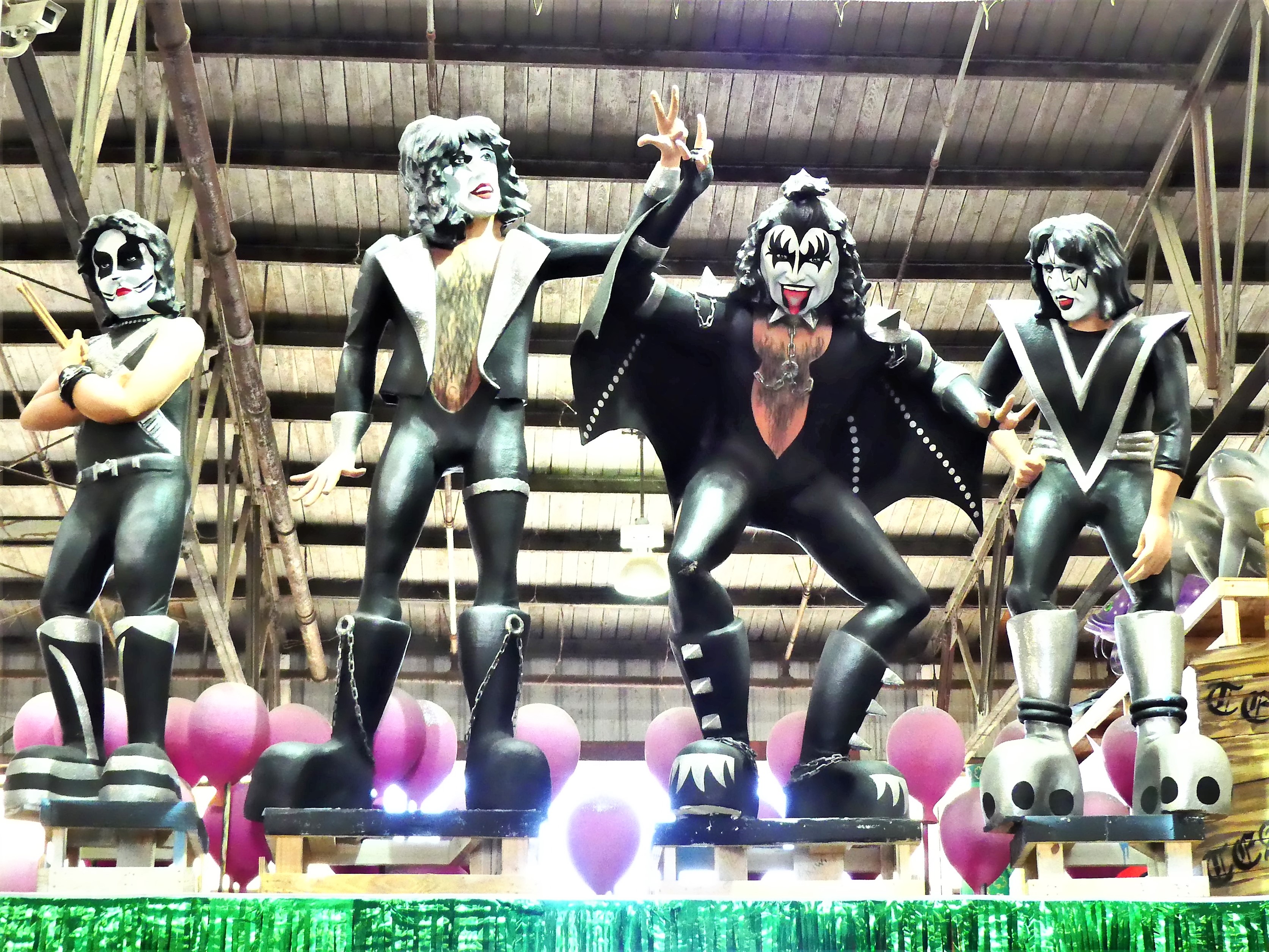

Since 1934, four generations of Kerns have been perfecting the art and business of celebrating Carnival, always managing year after year to surprise the public with fresh ideas infused with craftsmanship and technology.

Since 1934, four generations of Kerns have been perfecting the art and business of celebrating Carnival, always managing year after year to surprise the public with fresh ideas infused with craftsmanship and technology. Kern Studios works with dozens of carnival organizations (known as krewes) who finance their own parades through member dues and fund-raising to offset expenses for:

Kern Studios works with dozens of carnival organizations (known as krewes) who finance their own parades through member dues and fund-raising to offset expenses for: float warehousing, designing, sculpting, construction, decorating, tractor pulling, audio, lighting, and parade route security–all routinely costing $100,000 or more for each 28 foot display on wheels.

float warehousing, designing, sculpting, construction, decorating, tractor pulling, audio, lighting, and parade route security–all routinely costing $100,000 or more for each 28 foot display on wheels. But what’s a krewe to do if they eschew the usual bayou reissue? The Krewe of Bacchus commissioned Blaire to produce extravagant figures and floats on a more grandiose scale. He obliged them with 18 feet replicas of King Kong in 1972, and Queen Kong in 1973.

But what’s a krewe to do if they eschew the usual bayou reissue? The Krewe of Bacchus commissioned Blaire to produce extravagant figures and floats on a more grandiose scale. He obliged them with 18 feet replicas of King Kong in 1972, and Queen Kong in 1973.

…which makes it (big) easy to see why Mardi Gras is such a cash cow for New Orleans, and Blaire Kern,

…which makes it (big) easy to see why Mardi Gras is such a cash cow for New Orleans, and Blaire Kern, unless you’re a Buddhist.

unless you’re a Buddhist.

Our rack-for-two was prepared as 1/2 “wet” and 1/2 “dry”. The wet half was basted periodically with a rich tomato, molasses, and vinegar sauce laced with heat, while the dry half was rubbed in brown sugar and spices, rendering a caramelized crust during it’s 12 hour slow cook.

Our rack-for-two was prepared as 1/2 “wet” and 1/2 “dry”. The wet half was basted periodically with a rich tomato, molasses, and vinegar sauce laced with heat, while the dry half was rubbed in brown sugar and spices, rendering a caramelized crust during it’s 12 hour slow cook.

Fallingwater is considered the finest piece of mid-century architecture anywhere, and it’s a treat to tour the house from the perspective of the Kaufmann family, who commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design the retreat at the age of 70 in 1935. Completed in 1937 for $155,000, Wright frequently battled with Edgar Sr.–a Pittsburgh department store magnate–to preserve his purist design.

Fallingwater is considered the finest piece of mid-century architecture anywhere, and it’s a treat to tour the house from the perspective of the Kaufmann family, who commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design the retreat at the age of 70 in 1935. Completed in 1937 for $155,000, Wright frequently battled with Edgar Sr.–a Pittsburgh department store magnate–to preserve his purist design.