Today I met a national park service ranger by the name of A.L. Weimer who wore a bulletproof vest and carried a police-issue sidearm. While there are daily sightings of mountain lions and black bears throughout Big Bend National Park, I think his handgun has less to do with keeping the animals in line, and is more intended as a show of force in case any renegade Mexicans or Islamic terrorists get any big ideas about invading the U.S. through Mexico.

If so, Ranger Weimer, who manages the Boquillas Crossing, then becomes our first line of defense. Of course, thanks to our 2nd Amendment, I’m certain that many park visitors would rally in defense of our great nation, and arm themselves with the requisite arsenal of spatulas and Swiss army knives, or whatever else they could muster from their tents and RVs to hold off a foreign attack on American soil.

Leah and I decided that a reconnaissance mission was in order. To get to the other side, documents are first presented to Ranger Weimer, a dour-faced, no-nonsense bulldog, who makes sure there is no misunderstanding about the prohibition of alcohol or tobacco from abroad.

Walking through the customs house gate to the waterfront along a garden trail takes only five minutes.

The trail ends at a sandbar where eager Mexicans negotiate with Gringos to ferry them across the river by rowboat. Five dollars is generally the agreed upon price.

The trail ends at a sandbar where eager Mexicans negotiate with Gringos to ferry them across the river by rowboat. Five dollars is generally the agreed upon price.

However, with the Rio Grande water levels so low, Leah and I found it cheaper to wade across fifty feet of knee-deep water to the other side.

However, with the Rio Grande water levels so low, Leah and I found it cheaper to wade across fifty feet of knee-deep water to the other side.

Land transportation comes from Uber burros, charging five dollar fares to cover the dusty and shit-laden ¾-mile trip…

Land transportation comes from Uber burros, charging five dollar fares to cover the dusty and shit-laden ¾-mile trip…

…to a white trailer check-point surrounded by cyclone fencing on the edge of the village. It was a treat to sit in Boquillas’s only air conditioning for a few minutes to escape the 100◦ heat, while our identities were checked against a drug cartel database.

…to a white trailer check-point surrounded by cyclone fencing on the edge of the village. It was a treat to sit in Boquillas’s only air conditioning for a few minutes to escape the 100◦ heat, while our identities were checked against a drug cartel database.

Once Leah and I were cleared as respectable American citizens, we opted to lunch at the Original José Falcone’s Restaurant and Bar, the largest of two eateries in town…

…with an overlook of the Boquillas Canyon.

…with an overlook of the Boquillas Canyon.

Mama Falcone was sitting on the patio in her kitchen apron working on a future needlepoint tapestry that would soon display in the family curio shop next door, while her nephew Renaldo brought us menus and took our order—chicken quesadilla for Leah, and beef burrito for me. Meanwhile, a family of three from South Carolina sat at a nearby table chatting it up with Mama’s daughter, Lillia.

Mama Falcone was sitting on the patio in her kitchen apron working on a future needlepoint tapestry that would soon display in the family curio shop next door, while her nephew Renaldo brought us menus and took our order—chicken quesadilla for Leah, and beef burrito for me. Meanwhile, a family of three from South Carolina sat at a nearby table chatting it up with Mama’s daughter, Lillia.

Lillia was explaining that her father opened the restaurant in 1973 after a pickup truck accident put him in a wheelchair for the rest of his life. The restaurant was a big hit among locals and tourists, with Mama serving bean tacos and burritos, and Papa schmoozing the guests. Thanks to the unofficial crossing, villagers were accustomed to serving up to 200 Big Bend visitors a day—mostly tourists looking to enhance their park experience by buying food and souvenirs.

After Papa died in 2000, Mama and Lillia continued the business until the U.S. closed the border in May, 2002 in response to 9-11. Consequently, the town’s tourist trade dried up, and businesses failed without customers.

The town population shrank from three hundred to one hundred adults and children, with many leaving for Muzquiz—the nearest Mexican city, and a seven-hour bus ride away. Eventually, Mama and Lillia found work in the States, but returned home to the restaurant after the crossing officially reopened in April 2013.

The town population shrank from three hundred to one hundred adults and children, with many leaving for Muzquiz—the nearest Mexican city, and a seven-hour bus ride away. Eventually, Mama and Lillia found work in the States, but returned home to the restaurant after the crossing officially reopened in April 2013.

They are hopeful for an economic recovery, but the town is in shambles, and it will take many more Americans to salvage Boquillas’s economy.

They are hopeful for an economic recovery, but the town is in shambles, and it will take many more Americans to salvage Boquillas’s economy.

After lunch, Lillia volunteered Chico to drive us back to the landing in his beat-up Chevy Silverado. Chico was born and raised in Boquillas, and although his two brothers have moved on, he has never left.

“I like it here,” he admits. “It’s very quiet.”

When Chico isn’t shuttling visitors between the restaurant and the water, he bartends for the only bar in town, usually serving up beer to the locals. “Cervezza is cheap, but gas,” he explains, “is very expensive and hard to come by since Boquillas has no gas station. However, American friends are willing to fill five gallon containers from the park store, and send it over by boat.”

It occurred to me that Chico was giving us good intelligence about his situation, which would be useful should tensions ever flare between the U.S. and Mexico. And I believe that given the chance, Carrie Masterson and I could turn Chico into a valued asset. We tipped Chico five dollars for the ride and the invaluable information.

Leah and I crossed back the way we came—by wading through the Rio Grande. We acknowledged Ranger Weimer upon our return, who ushered us to a virtual customs station, where we submitted our credentials electronically and spoke by phone to an invisible agent who scanned us by remote camera.

“Take off your hat, remove your sunglasses, and stand behind the yellow line,” barked the long-distance voice.

After answering a few routine questions, like “Are you bringing any raw fruits or vegetables into the country?”, we were safely readmitted to America.

Turning to Ranger Weimer, I asked casually, “So how do you feel about Trump building a Wall down here?

He looked at me sternly, and answered in a stoic voice, “Sir, we’re not allowed to express an opinion about that matter.”

But I wasn’t done yet. “But do you think these people are dangerous?”

He was becoming annoyed, answering more emphatically, “Like I said, sir; I have no opinion on the matter!”

I left Boquillas Crossing completely satisfied by our cultural exchange, and reassured that we would be safe from bad hombres from the other side. Fortunately for us, the citizens of Boquillas del Carmen are hard-working people. They are a small and subdued militia of struggling entrepreneurs who depend on us, and are more interested in fighting for their livelihood than picking a fight with their neighbor.

I have met the enemy face to face and I do not fear them. Their rowboats and mules would be no match against our ships and tanks.

I have met the enemy face to face and I do not fear them. Their rowboats and mules would be no match against our ships and tanks.

The trail ends at a sandbar where eager Mexicans negotiate with Gringos to ferry them across the river by rowboat. Five dollars is generally the agreed upon price.

The trail ends at a sandbar where eager Mexicans negotiate with Gringos to ferry them across the river by rowboat. Five dollars is generally the agreed upon price. However, with the Rio Grande water levels so low, Leah and I found it cheaper to wade across fifty feet of knee-deep water to the other side.

However, with the Rio Grande water levels so low, Leah and I found it cheaper to wade across fifty feet of knee-deep water to the other side. Land transportation comes from Uber burros, charging five dollar fares to cover the dusty and shit-laden ¾-mile trip…

Land transportation comes from Uber burros, charging five dollar fares to cover the dusty and shit-laden ¾-mile trip… …to a white trailer check-point surrounded by cyclone fencing on the edge of the village. It was a treat to sit in Boquillas’s only air conditioning for a few minutes to escape the 100◦ heat, while our identities were checked against a drug cartel database.

…to a white trailer check-point surrounded by cyclone fencing on the edge of the village. It was a treat to sit in Boquillas’s only air conditioning for a few minutes to escape the 100◦ heat, while our identities were checked against a drug cartel database. …with an overlook of the Boquillas Canyon.

…with an overlook of the Boquillas Canyon. Mama Falcone was sitting on the patio in her kitchen apron working on a future needlepoint tapestry that would soon display in the family curio shop next door, while her nephew Renaldo brought us menus and took our order—chicken quesadilla for Leah, and beef burrito for me. Meanwhile, a family of three from South Carolina sat at a nearby table chatting it up with Mama’s daughter, Lillia.

Mama Falcone was sitting on the patio in her kitchen apron working on a future needlepoint tapestry that would soon display in the family curio shop next door, while her nephew Renaldo brought us menus and took our order—chicken quesadilla for Leah, and beef burrito for me. Meanwhile, a family of three from South Carolina sat at a nearby table chatting it up with Mama’s daughter, Lillia. The town population shrank from three hundred to one hundred adults and children, with many leaving for Muzquiz—the nearest Mexican city, and a seven-hour bus ride away. Eventually, Mama and Lillia found work in the States, but returned home to the restaurant after the crossing officially reopened in April 2013.

The town population shrank from three hundred to one hundred adults and children, with many leaving for Muzquiz—the nearest Mexican city, and a seven-hour bus ride away. Eventually, Mama and Lillia found work in the States, but returned home to the restaurant after the crossing officially reopened in April 2013. They are hopeful for an economic recovery, but the town is in shambles, and it will take many more Americans to salvage Boquillas’s economy.

They are hopeful for an economic recovery, but the town is in shambles, and it will take many more Americans to salvage Boquillas’s economy.

I have met the enemy face to face and I do not fear them. Their rowboats and mules would be no match against our ships and tanks.

I have met the enemy face to face and I do not fear them. Their rowboats and mules would be no match against our ships and tanks.

Earlier in the day, border patrol had sped past our campsite from the southern border, causing us to speculate whether an ICE officer had just interdicted an illegal border crosser. And so, with the sun at our backs, and our batteries recharged, I fired up the F-150, turned right on Texas FM (farm-to-market road) 2627, and headed due south in search of bad hombres. The radio god immediately synchronized his playlist with our mission, and delivered David Byrne belting out the lyrics to “We’re on the Road to Nowhere”.

Earlier in the day, border patrol had sped past our campsite from the southern border, causing us to speculate whether an ICE officer had just interdicted an illegal border crosser. And so, with the sun at our backs, and our batteries recharged, I fired up the F-150, turned right on Texas FM (farm-to-market road) 2627, and headed due south in search of bad hombres. The radio god immediately synchronized his playlist with our mission, and delivered David Byrne belting out the lyrics to “We’re on the Road to Nowhere”. Historically, the bridge was constructed by Dow Chemical in 1964 to transport fluorite from Coahuilan mines across Heath Canyon to America. But U.S. and Mexican authorities shuttered the bridge in 1997, suspecting drug smuggling. Other reports cite the murder of a Mexican customs official as the reason behind the bridge closure.

Historically, the bridge was constructed by Dow Chemical in 1964 to transport fluorite from Coahuilan mines across Heath Canyon to America. But U.S. and Mexican authorities shuttered the bridge in 1997, suspecting drug smuggling. Other reports cite the murder of a Mexican customs official as the reason behind the bridge closure. Across the border stand the remnants of a faded factory.

Across the border stand the remnants of a faded factory. Broken buildings and slanted warehouses survive in silence against a brown mountain backdrop.

Broken buildings and slanted warehouses survive in silence against a brown mountain backdrop. Yet in the distance to the right of the river, La Linda mission stands alone—its double towers dwarfed by nature’s majesty, and its church doors removed for a purpose higher than God.

Yet in the distance to the right of the river, La Linda mission stands alone—its double towers dwarfed by nature’s majesty, and its church doors removed for a purpose higher than God. There are those who would welcome a return to the border crossing.

There are those who would welcome a return to the border crossing. Committee meetings and feasibility studies on both sides of the river argue the benefits of potential tourism and ease of crossing without traveling to either Del Rio or Presidio. Currently, a legal crossing to La Linda would take nearly 10 hours by car versus 10 minutes by illegal foot path. But there are no travelers today, or at any other times. It’s just too remote.

Committee meetings and feasibility studies on both sides of the river argue the benefits of potential tourism and ease of crossing without traveling to either Del Rio or Presidio. Currently, a legal crossing to La Linda would take nearly 10 hours by car versus 10 minutes by illegal foot path. But there are no travelers today, or at any other times. It’s just too remote.

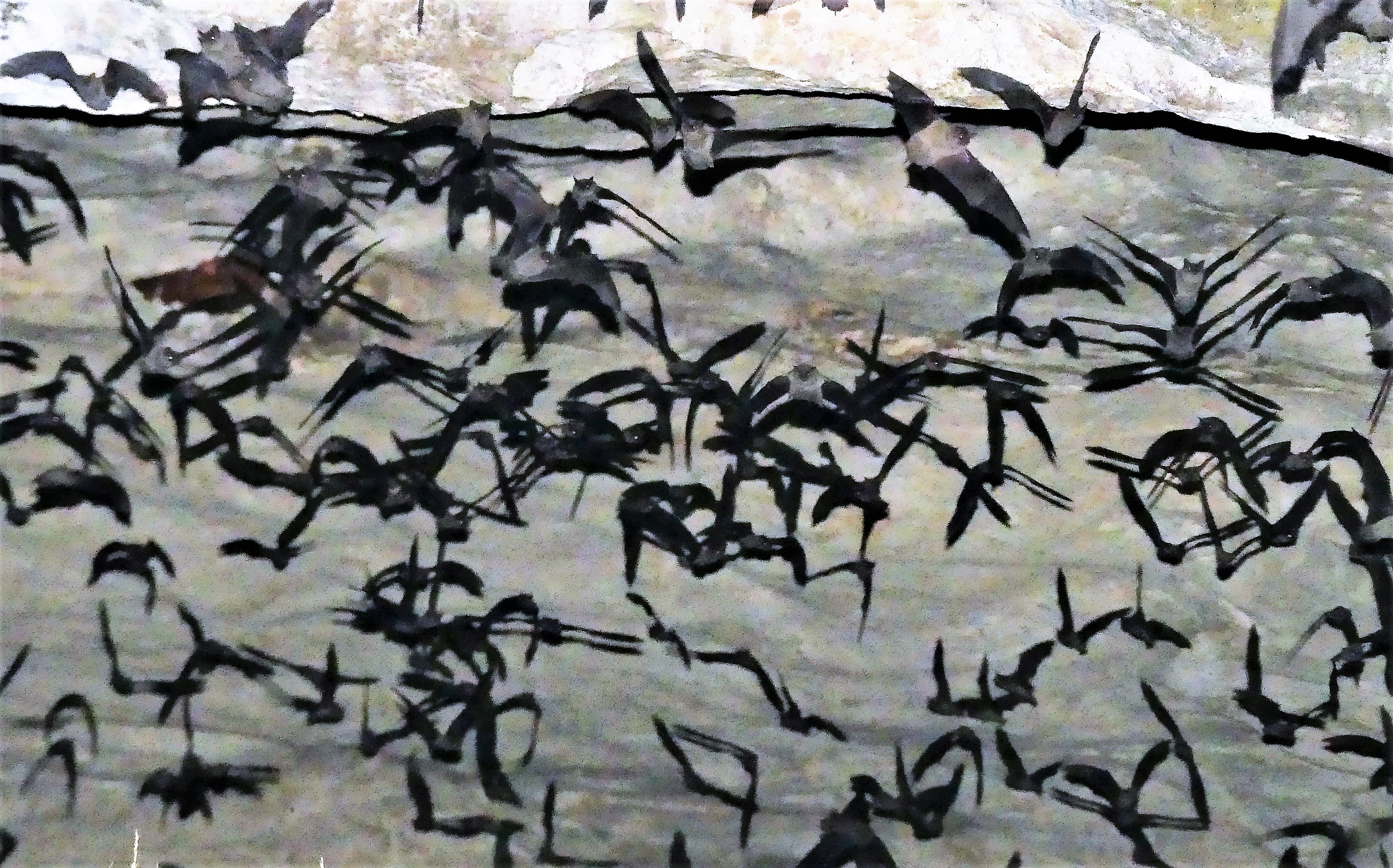

and into the twilight, fluttering en masse, up and over the trees.

and into the twilight, fluttering en masse, up and over the trees. A continuous and frenzied swarm pours from the cave in a procession that could last up to two hours.

A continuous and frenzied swarm pours from the cave in a procession that could last up to two hours. With the exception of some rogue bats that fly off in scattered directions, the mother lode hooks right and follows a path 50 miles due east to Uvalde in search of mosquitoes and corn earworms, a tasty moth that wreaks havoc on a number of Southern crops.

With the exception of some rogue bats that fly off in scattered directions, the mother lode hooks right and follows a path 50 miles due east to Uvalde in search of mosquitoes and corn earworms, a tasty moth that wreaks havoc on a number of Southern crops. Historically, the Sergeant family, who farmed this property from the early 1900’s, protected the cave entrance with fencing in order to mine the accumulated guano, which provided important income to the ranchers until 1957 when sold as premium fertilizer and an explosive constituent.

Historically, the Sergeant family, who farmed this property from the early 1900’s, protected the cave entrance with fencing in order to mine the accumulated guano, which provided important income to the ranchers until 1957 when sold as premium fertilizer and an explosive constituent. Having over-nighted for three days in the park, I can testify that there is no shortage of annoying bugs here. Not to be selfish, but I’d like to propose that some of the bats stay behind and clean up inside the park’s perimeter. If the bats only knew that they could dine closer to home–forsaking the 100-mile round-trip–then I could better enjoy my outdoor dinner plans as well.

Having over-nighted for three days in the park, I can testify that there is no shortage of annoying bugs here. Not to be selfish, but I’d like to propose that some of the bats stay behind and clean up inside the park’s perimeter. If the bats only knew that they could dine closer to home–forsaking the 100-mile round-trip–then I could better enjoy my outdoor dinner plans as well.

or find a blanket-sized parcel of grass to relax and watch the sun go down;

or find a blanket-sized parcel of grass to relax and watch the sun go down; or pull up in a boat to wait for showtime.

or pull up in a boat to wait for showtime. One fellow standing behind me seems to be mystified by the whole experience. “Are they gonna fly outta that sewer hole over there?” he wonders out loud.

One fellow standing behind me seems to be mystified by the whole experience. “Are they gonna fly outta that sewer hole over there?” he wonders out loud. His misconception is immediately corrected by a 10-year old standing nearby. “Hey mister, this isn’t Batman, y’know! They come out from under the bridge where they live,” says Einstein boy.

His misconception is immediately corrected by a 10-year old standing nearby. “Hey mister, this isn’t Batman, y’know! They come out from under the bridge where they live,” says Einstein boy. I too am excited to catch the bats in flight, but I’m also interested in doing something different with my Lumix, which I’m still learning to use. I’m determined to capture the bats in motion!

I too am excited to catch the bats in flight, but I’m also interested in doing something different with my Lumix, which I’m still learning to use. I’m determined to capture the bats in motion! The moment arrives when the first bats emerge, and the crowd gets giddy.

The moment arrives when the first bats emerge, and the crowd gets giddy. And moments later, the floodgates open, and the bats streak across the night sky by the thousands–

And moments later, the floodgates open, and the bats streak across the night sky by the thousands– a migration wave of epic proportions that approaches a feeding frenzy.

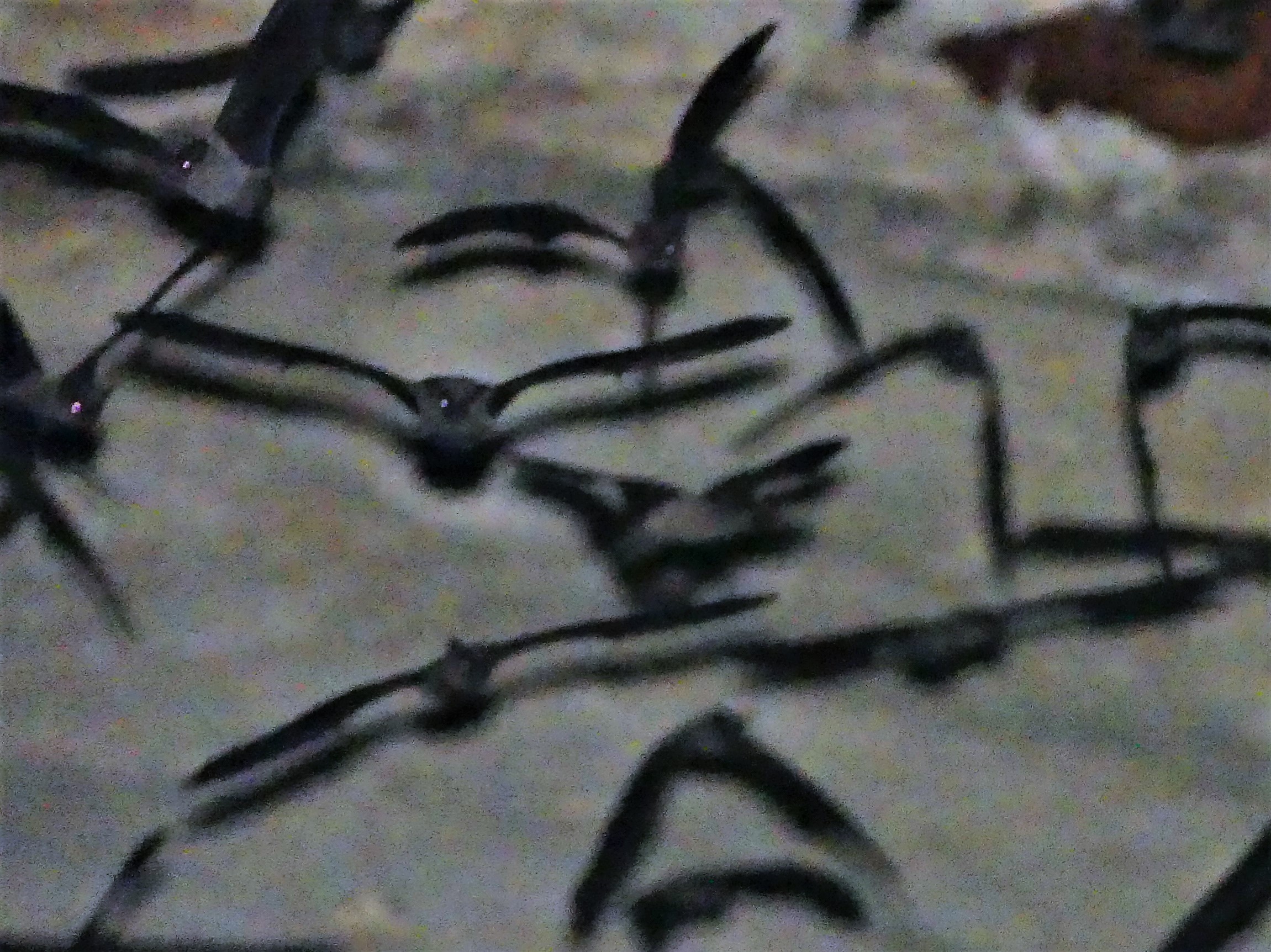

a migration wave of epic proportions that approaches a feeding frenzy. I confess that the photos are experimental. However, I understand that there are traditionalists who need to see things as they are, versus my interpretation of the event. So, in fairness to those whose vision is less oblique than mine, I’ve increased the camera’s shutter speed to give a more accurate representation of the bats’ flight path…

I confess that the photos are experimental. However, I understand that there are traditionalists who need to see things as they are, versus my interpretation of the event. So, in fairness to those whose vision is less oblique than mine, I’ve increased the camera’s shutter speed to give a more accurate representation of the bats’ flight path… such that even Meat Loaf would be impressed.

such that even Meat Loaf would be impressed.

The other condition is a more common affliction commonly known as drifting-into-ditch-itis.

The other condition is a more common affliction commonly known as drifting-into-ditch-itis.