Three months of rigorous physical therapy during a summer of exhausting humidity, sweltering heat, and heavy downpours was a poor substitute for the summer adventure that Leah and I originally plotted together at the kitchen counter one year ago.

We imagined Airstreaming up to Quebec to play in Saguenay Fjord National Park and be entertained by French Canadians for a month or so.

Of course, nothing went as planned. My shoulder surgery and subsequent physical therapy replaced our summer trip to the North Country.

But putting in the hard work also guaranteed us a summer redo Down Under, with a chance to celebrate Hanukkah in New Zealand and Christmas Day in Melbourne.

It was also a good excuse for a new camera… system, unlike last year’s trip to Southeast Asia, where I relied exclusively on my Samsung Galaxy S23 Ultra for images and video.

But for a trip to my 7th recorded continent, I yearned to compose through a viewfinder again. Ultimately, I thought a mirrorless compact camera’s flexibility and versatility could empower me to take bigger chances and create better photographs.

So, I bought a Fujifilm X-E5.

It may have been a bit impulsive, buying before trying, but Fuji’s model was brand new, very popular and not widely available. Camera exchanges were quickly selling out limited inventory across the globe, despite the high price, plus the tariff surcharge. (Yes, the tariff/tax is passed on to consumers!) I was betting on the buzz and positive reviews, and went all-in.

Outfitted with Fuji XF 16-50mm f/2.8-4.8 and Fuji XF 70-300mm f/4-5.6., I now had a wide and long zoom for a variety of coverage.

It was also a light-weight travel kit designed to reduce the camera strap impression across my newly, reassembled rotator cuff.

It would be a glorious second-chance summer.

Leah and I figured on an extra day in Aukland to cover our cancellation-du-jour asses from airline exposure, and to bolster our recovery from a lost day and a 20-hour trip…

Although our business class cocoons…

offered legitimate restorative properties.

Checking into the Grand by SkyCity put us smack dab in the center of Auckland’s bustling entertainment and casino complex, where the Sky Tower’s the limit.

Our 220-meter ascent to the 60th floor observation deck gave us distant perspective…

and telephoto detail with my new Fuji kit…

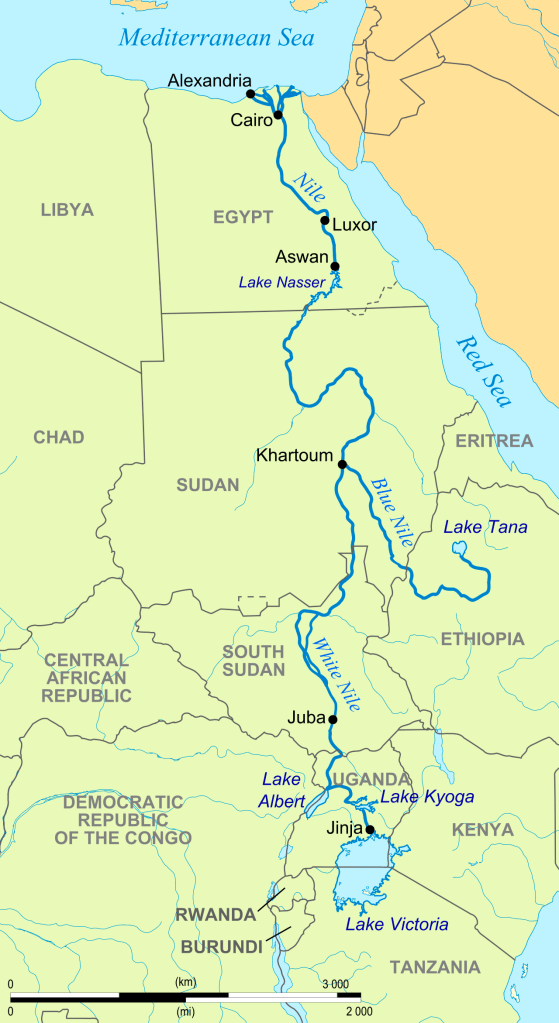

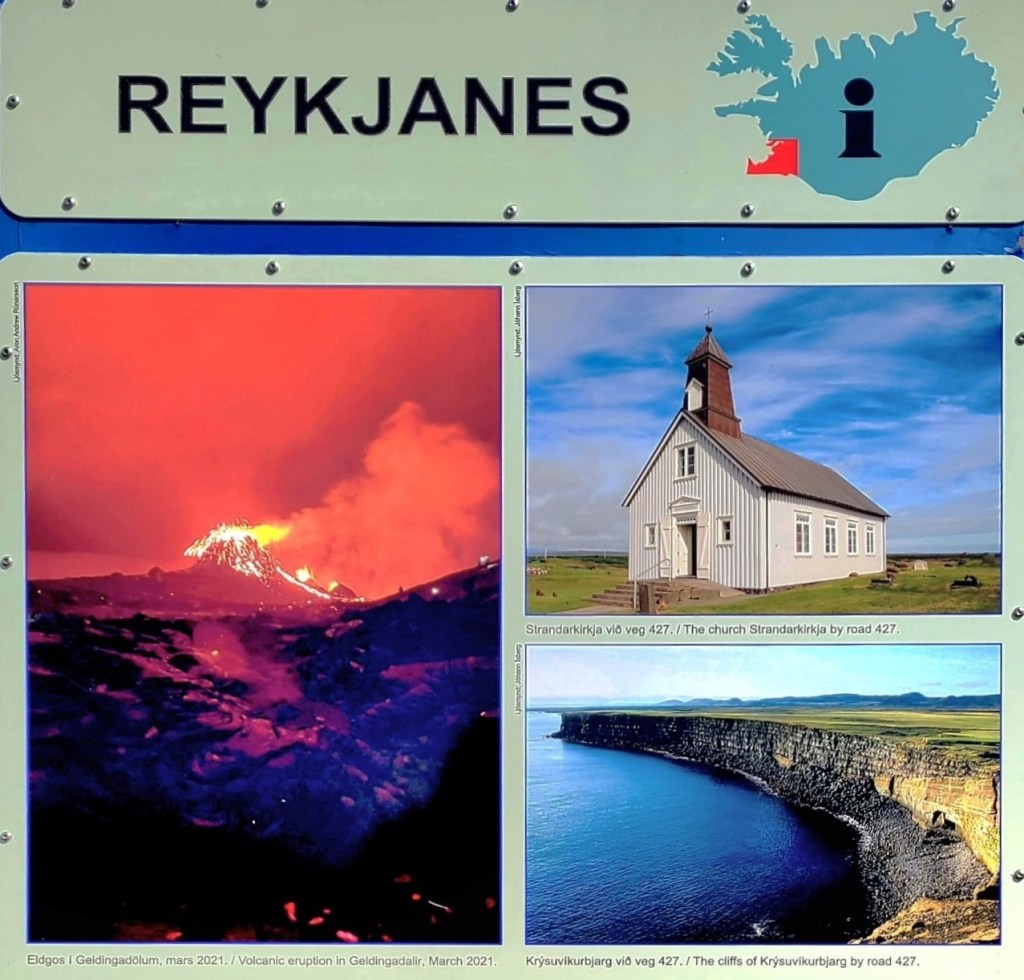

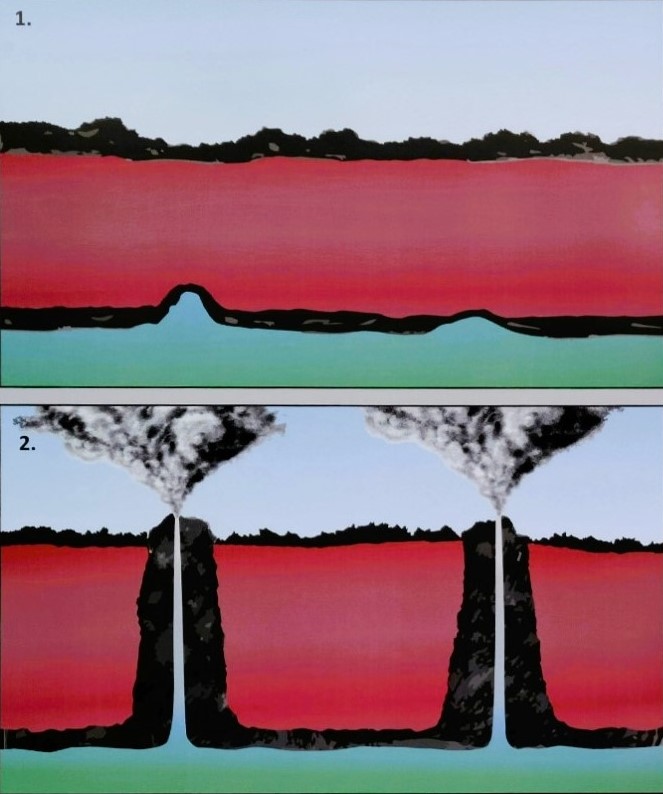

With time to burn, we set our sights on the quaint town of Devonport, one of 53 dormant volcanic centers surrounding Auckland.

Christmas was on full display in the city plazas…

as we strolled to Queens Wharf to catch our ferry across Stanley Bay.

However, the crimson blossoms from the Pōhutukawa trees (aka New Zealand Christmas tree) along Devonport’s park path easily enhanced the holiday vibe.

We hiked to Mount Victoria (Takarunga), Devonport’s highest point atop a WWII bunker–currently the local folk music center–that breathes through its field of mushroom ventilation caps,

where our climb was rewarded with an exquisite view of the city.

Tomorrow, our Viking cruise extension starts in earnest, with a trip to Waiheke Island.