It’s always a good day when it starts with a waterfall and ends with a waterfall. Prior to today, all the designated waterfalls on our itinerary over the past eight days have been spectacular and very different from one another–given the geography, the weather conditions, the time of day, and the lighting–all of which has an impact on how the falls are viewed and captured.

Thankfully, today was no different!

After a restful overnight and an enjoyable breakfast buffet at Hofsstaðir Guesthouse in Skagafjörður,

Leah and I evaluated today’s weather, and sighed with relief knowing that overcast skies would fight off any imminent threat of rain. Maybe our prayers had been answered.

Of all our scheduled excursions, we were most excited about riding an Icelandic horse, and rain would certainly dampen the experience. We cautiously saddled up the Land Cruiser,

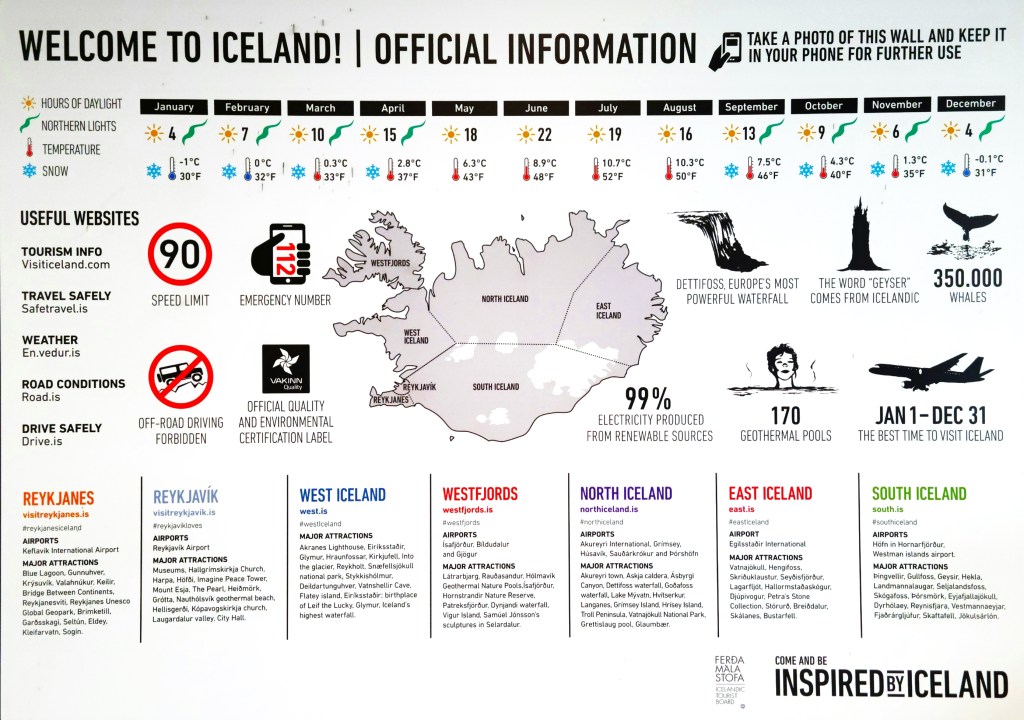

and patiently waited for our Hitachi Wi-Fi dongle (a very neat accessory) to find my phone. Eventually, we plotted a route to Hestasport, a tour company operating within the Skagafjörður valley–a place that’s been labeled the Mecca of Icelandic horsemanship, and the only county in Iceland where horses outnumber people.

Our conversation to the horse ranch was predictable. Leah and I were still processing the irony of our hotel restaurant serving “horse” on last night’s dinner menu. Of course, its a cultural and culinary delicacy that Icelanders have enjoyed since purebred Nordic horses were first introduced during the 9th century. And horsemeat is one of the healthiest meats for human consumption–iron-rich, low-fat and abundant in vitamin B. But our American palates and sensibilities are biased. We find that butchering horses for human fodder is morally abhorrent, while still enjoying a rib eye beefsteak. So, guilty of hypocrisy, as charged.

After arriving at Hestasport for our 10 o’clock “Viking ride,”

we gathered in the barn to dress for rain, then greeted our riding buddies in the paddock.

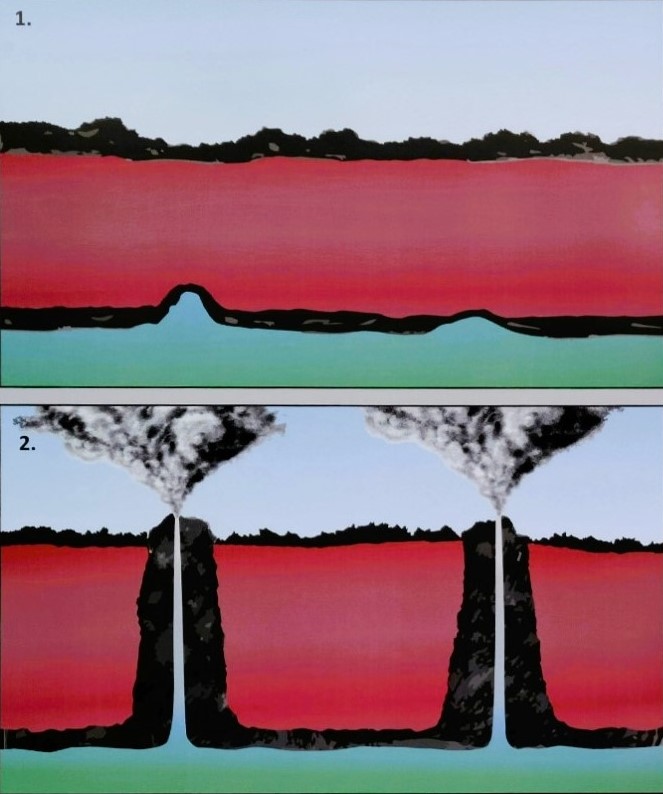

Icelandics have been strictly inbred for riding and working over a millennium, which makes them nearly disease-free and extremely resilient to Iceland’s harsh climate. They can easily live into their 50s. They have a friendly personality and a special affinity for people.

Leah was assigned Bjartur, while I would be riding Björn, an agreeable 23-year old, who was the only one of the herd who could fly–the fastest of five gaits (up to 30 mph) that Icelandics naturally possess.

My first impressions of Icelandics…they are small, but sturdy and capable. While their legs are short (they typically stand 13 hands on average), they are capable of carrying up to 35% of their body weight. When they walk, their head is down and neck relaxed, which gives them a straight line across their back to evenly support the carrying weight.

Their walk is smooth and sure-footed, which easily accommodates uneven landscape and shallow rivers.

We closely followed the river Svartá at a steady pace, allowing us to soak in the scenery. Our guides were ingenues from Belgium and Holland, who were mostly shepherding a German family of four with little experience, but our Icelandics were very forgiving. They took to the trail they’ve known since foals, so the Germans were on solid footings.

But I was looking for something more. I was hoping to tölt, a oft-touted gait that’s exclusive to Icelanders, where the horse lifts its front leg up high, and only one foot touches the ground at any time. When we reached a level open field, Bridgette from Brussels shortened the reins of her horse, which immediately caused her horse to tölt, and immediately cued my horse to copy. I was tölting! Björn gave a smooth-paced ride with minimal bounce, as he glided over the gravelly terrain. It was exhilarating, but short-lived as we reached our destination much too soon to stop. But in exchange, we were humbled by a view of Reyjafoss.

Leah and I returned to our Land Cruiser to explore our next major destination, the Westfjords. But first, we detoured to the Vatnsnes peninsula, where iconic basalt stacks line the shore,

and volcanic sands sharply contrast against distant snow caps.

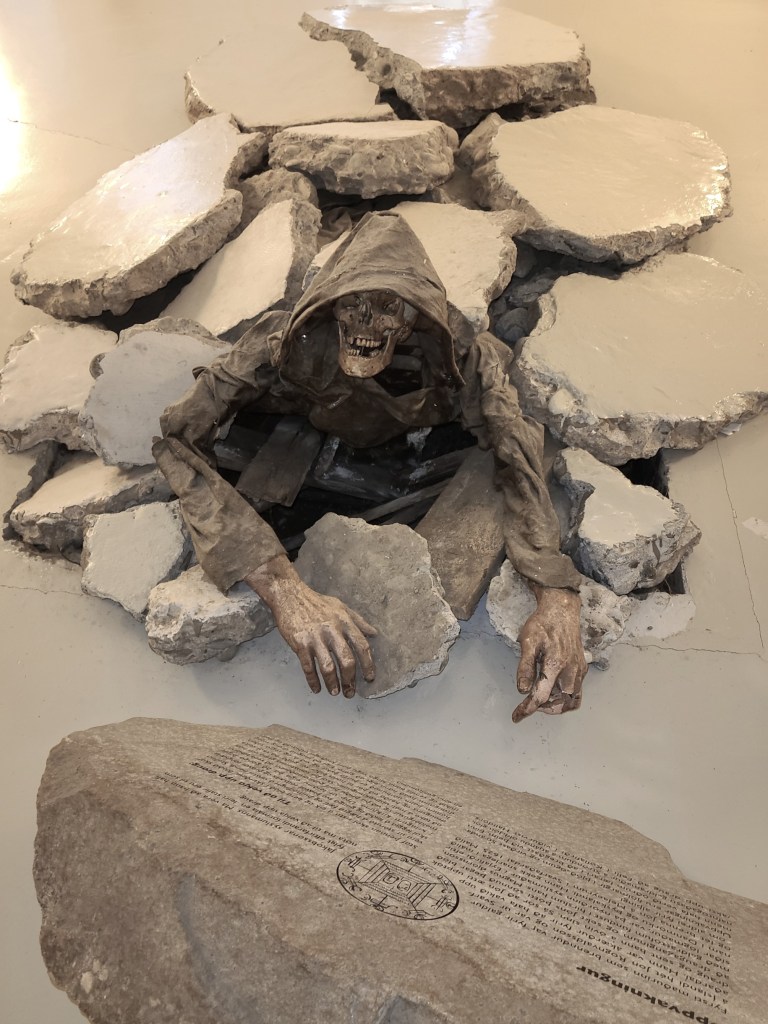

We bookended our day’s tour with a drive to Kolugljúfur Canyon, hoping to find Kola, a legendary giantess who dwelled in the canyon.

Her daily ritual of fishing and preparing salmon helped to shape the gorge.

Alas, Kola was nowhere to be found, but we discovered her hiding place; it was Kolufoss.

and it was too beautiful to disturb her.