There’s very little to write about Frank Lloyd Wright that scholars haven’t already written.

His affinty for nature, his indefatigable energy, his genius for design, his eagerness to experiment, his immense ego, his appetite for women, his dedication to family–it’s all been revealed and discussed in numerous books and lectures. But it’s also apparent from walking through his Taliesin estate in Spring Green, Wisconsin.

Leah and I would have preferred the immersive, 4-hr Estate Tour, but when I checked on-line for tickets, only one ticket was available when I needed two. It seems that no tour exceeds 21 people, matching the number of seats on the shuttle. Instead, we opted for the 2-hr Highlights Tour.

We boarded the bus at the Visitor Center–

orginally designed by Wright in 1953 as a restaurant and “gateway” to Taliesin, but Wright’s death in 1959 stalled any further construction until his former apprentices completed the building in 1967.

The ride took us past Midway Barn, Uncle John’s farming complex,

on the way to Hillside, the site of the home school he built for his Aunts Jane and Ellen Lloyd Jones.

Currently, the building is occupied by a time-shared architecture “Fellowship”–funded by the Taliesin Foundation–that occaisionally gathers in the Assembly Hall,

and takes meals in the Fellowship Dining Room,

before returning to the 5,000 sq. ft. “abstract forest” Drafting Studio.

We finished up at Wright’s intimate, 120-seat Hillside Theater–originally intended as a gymnasium, but converted by Wright to a cultural space after determining that the arts were more important than sports–

and reboarded the bus for a brief blast of air conditioning and quick trip to Wright’s home studio,

where we browsed through a drafting room filled with “Usonian” models, like the Willey House from 1934,

and assorted personal artifacts.

The house was noticably cooler, thanks to geothermal plumbing installed during the third re-build. We rounded the studio from the outside,

walked across a mound with views of the restored Romeo and Juliet windmill,

and traversed the gardens,

before re-entering the house through the expansive living room,

filled with wonderful flourishes, like glass-cornered windows (which Wright would ultimately perfect at Fallingwater)…

built-in table lamps,

and integration of sculptures that survived the previous two house fires.

Roaming through Wright’s personal bedroom (because he was an insomniac), we discovered no door, a wall of windows without window treatments, and original electric- blue shag carpeting.

The terrace offered glorious views of the Wisconsin River and Tower Hill State Park,

and Unity Chapel in the distance–

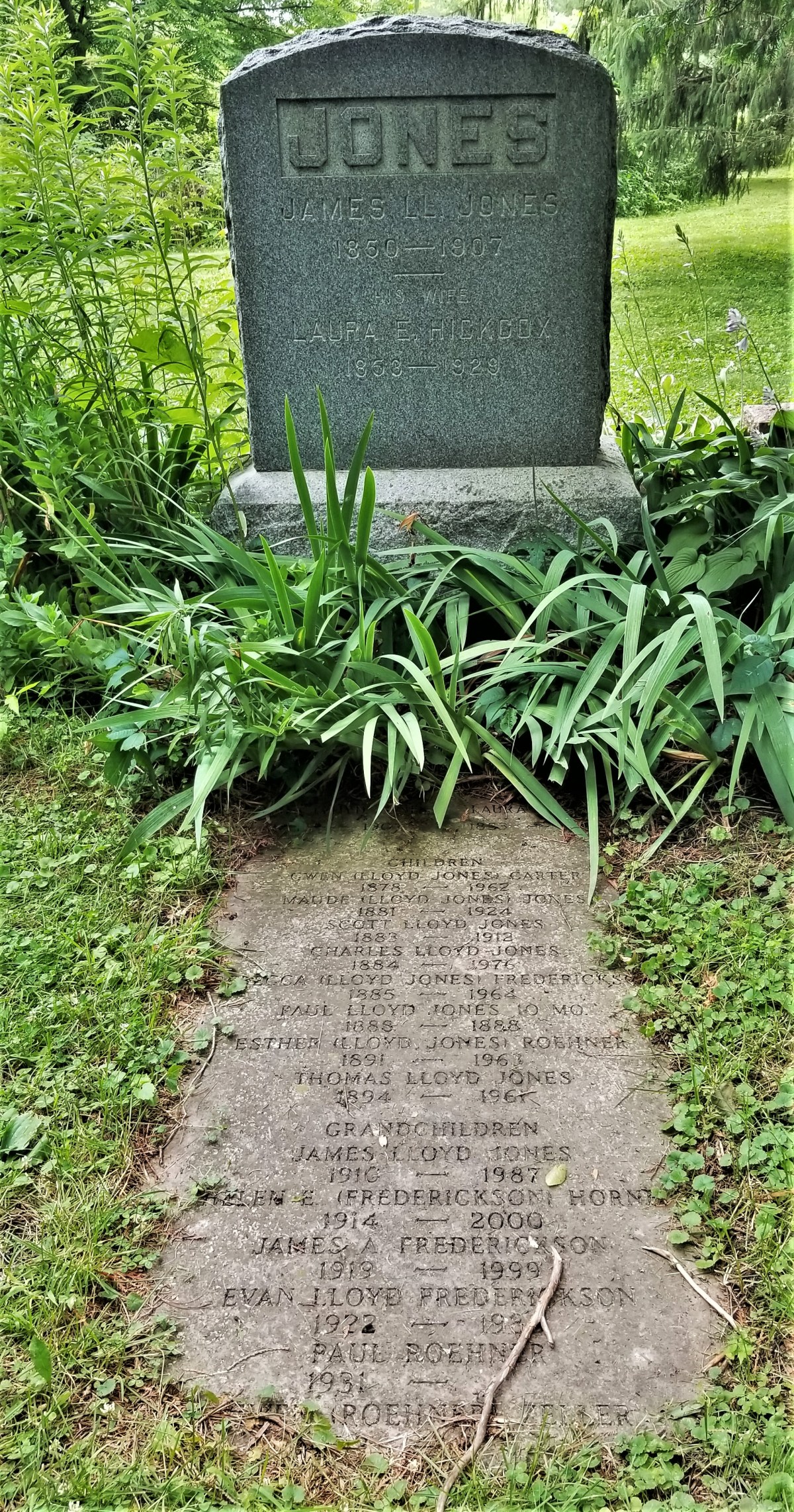

the site of Wright’s maternal family’s burial plots, his stone marker, and his empty grave.

As our driver passed Wright’s man-made falls,

our docent passed along a local story of intrigue and scandal:

During March 25, 1985, under cover of darkness, Frank Lloyd Wright’s body was exhumed from his Unity Chapel resting place by his oldest granddaughter, Elizabeth Wright Ingraham, and moved to a burial site at Taliesin West, in Scottsdale, Arizona.

She claimed to be fulfilling the dying wishes of her grandmother and Wright’s widow, Olgivanna Lloyd Wright, whose ashes were united with her husband’s within a memorial wall overlooking Paradise Valley. The event sparked outrage around the globe from associates and friends who argued that the architect would have desired to spend eternity at Unity Church with his family.

Even now, Spring Green residents hope that one day their favorite son will get his ash back to Wisconsin.

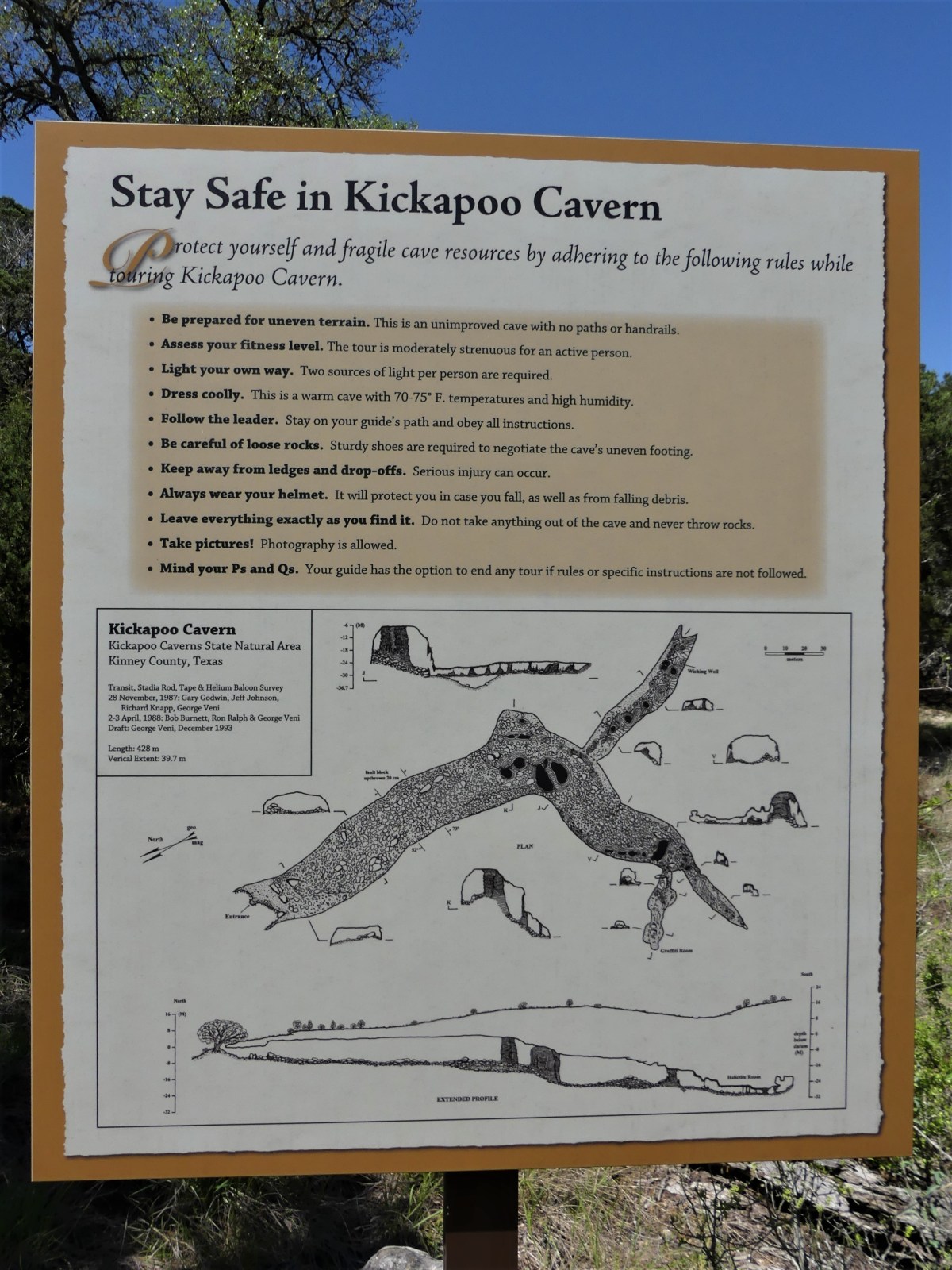

After listening to Ranger Matt’s presentation, I have a personal theory why natives might have avoided the cave. It seems that during the cold winter months, the cave acts as a warm weather haven for Indiana Jones’ worst nightmare. Only until the weather heats up outside, and all the good snakes wind their way out of their cozy cave den is it safe for humans to explore the inner depths, and that’s where master spelunker Ranger Matt was taking us.

After listening to Ranger Matt’s presentation, I have a personal theory why natives might have avoided the cave. It seems that during the cold winter months, the cave acts as a warm weather haven for Indiana Jones’ worst nightmare. Only until the weather heats up outside, and all the good snakes wind their way out of their cozy cave den is it safe for humans to explore the inner depths, and that’s where master spelunker Ranger Matt was taking us. “That explains the bullet hole in the windshield,” I presumed.

“That explains the bullet hole in the windshield,” I presumed. Bertha had been given a pardon, only to be reincarnated as a park bus. For some reason, I was reminded of a road sign I spied on the way to Kickapoo that read: DO NOT PICK UP HITCHHIKERS. THEY MAY BE PRISON ESCAPEES.

Bertha had been given a pardon, only to be reincarnated as a park bus. For some reason, I was reminded of a road sign I spied on the way to Kickapoo that read: DO NOT PICK UP HITCHHIKERS. THEY MAY BE PRISON ESCAPEES. checking for varmints before allowing us to climb through a small crack in the ground,

checking for varmints before allowing us to climb through a small crack in the ground, where we found ourselves standing on the collapsed ceiling of a limestone rock pile measuring 130 feet thick. The mouth of the room was big enough to park a Cessna if you could figure a way to get it inside.

where we found ourselves standing on the collapsed ceiling of a limestone rock pile measuring 130 feet thick. The mouth of the room was big enough to park a Cessna if you could figure a way to get it inside. and more recent remains of an unfortunate sheep or goat littering the floor

and more recent remains of an unfortunate sheep or goat littering the floor From there we dropped approximately 40 feet, scrambling over ledges of flat rock and boulders, on our way to survey the three largest columns (when a stalactite meets a stalagmite) in Texas. How apropos that along the way, we would pass a formation of stalactites that managed to aggregate into the shape of the Lone Star state.

From there we dropped approximately 40 feet, scrambling over ledges of flat rock and boulders, on our way to survey the three largest columns (when a stalactite meets a stalagmite) in Texas. How apropos that along the way, we would pass a formation of stalactites that managed to aggregate into the shape of the Lone Star state. There was no meaningful trail. Every step was a floating rock, see-sawing under our weight. That’s when I heard Leah go down hard behind me. I swung around to see her flat on her back, saved by her fanny pack.

There was no meaningful trail. Every step was a floating rock, see-sawing under our weight. That’s when I heard Leah go down hard behind me. I swung around to see her flat on her back, saved by her fanny pack. And Matt was there in an instant.

And Matt was there in an instant. “I’m alright,” she declared. “I just lost my balance on the rocks.” It was good news to my ears. For some reason, Leah and caves are not on equal footing, and rarely without incident (see “A Hole in the Head” post),

“I’m alright,” she declared. “I just lost my balance on the rocks.” It was good news to my ears. For some reason, Leah and caves are not on equal footing, and rarely without incident (see “A Hole in the Head” post),

We turned the corner and the room opened up. The ceiling vaulted higher to accomodate the caves’s largest column.

We turned the corner and the room opened up. The ceiling vaulted higher to accomodate the caves’s largest column. “Don’t be afraid to touch anything,” announced Ranger Matt. “We’re not like most of those other parks that have guard rails and ropes, and psychedelic lights with church music playing.” He was preaching to my choir.

“Don’t be afraid to touch anything,” announced Ranger Matt. “We’re not like most of those other parks that have guard rails and ropes, and psychedelic lights with church music playing.” He was preaching to my choir. “Like this one over here?” suggested a blond coed, pointing to a name scratched into the calcite that dated back to 1887.

“Like this one over here?” suggested a blond coed, pointing to a name scratched into the calcite that dated back to 1887. “Ah, good ol’ C. Robinson,” Ranger Matt explained, “He was one of the early ones. But there’s older graffiti in this cave that predates Mr. Robinson–written with torch soot–but that’s in a room that’s off limits because it’s still developing.”

“Ah, good ol’ C. Robinson,” Ranger Matt explained, “He was one of the early ones. But there’s older graffiti in this cave that predates Mr. Robinson–written with torch soot–but that’s in a room that’s off limits because it’s still developing.” We solemnly wove our way around the space, beholding the nascent natural beauty that will one day become a future column.

We solemnly wove our way around the space, beholding the nascent natural beauty that will one day become a future column.

Fallingwater is considered the finest piece of mid-century architecture anywhere, and it’s a treat to tour the house from the perspective of the Kaufmann family, who commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design the retreat at the age of 70 in 1935. Completed in 1937 for $155,000, Wright frequently battled with Edgar Sr.–a Pittsburgh department store magnate–to preserve his purist design.

Fallingwater is considered the finest piece of mid-century architecture anywhere, and it’s a treat to tour the house from the perspective of the Kaufmann family, who commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design the retreat at the age of 70 in 1935. Completed in 1937 for $155,000, Wright frequently battled with Edgar Sr.–a Pittsburgh department store magnate–to preserve his purist design.