BREAKING NEWS

Ordinarily, I’d be blogging about my summer road trip to Quebec’s National Parks, with occasional lookbacks to our winter adventures in Vietnam. But circumstances have changed, and future long-distance travel has been placed on hold until October.

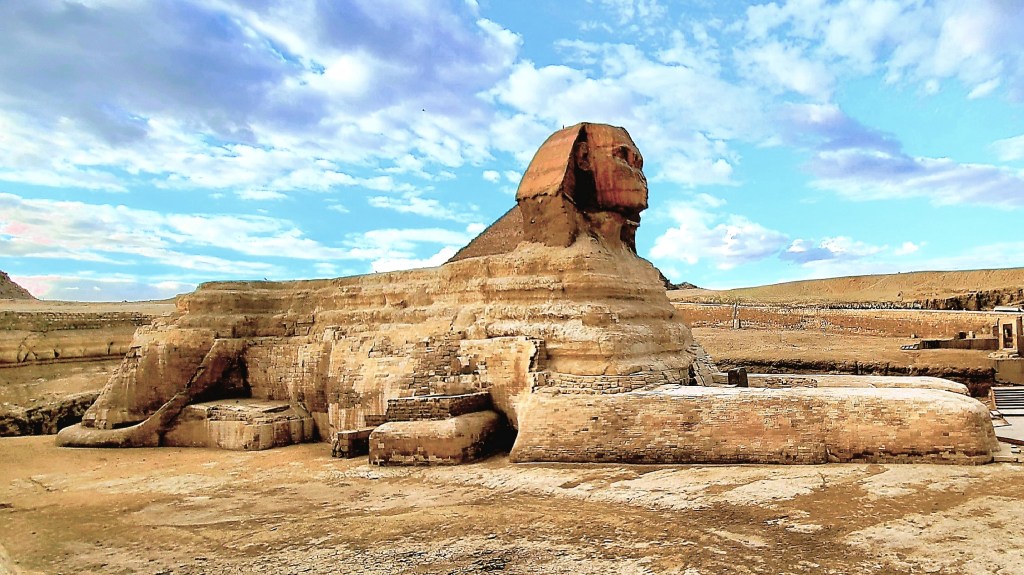

Instead, I’ll be introducing a new cycle of posts reflecting my road to recovery after emergency rotator cuff surgery on my right shoulder. And, I’m using a photo of a famous location in Door County taken 6 summers ago, which may seem like a metaphorical cliche, but it still rings true in consideration of my latest debacle.

Let me explain.

About 35 years ago, I joined a neighborhood softball league as a catcher. During a particularly fateful game near the end of our schedule, a batter hit a routine flyball to shallow left field with a runner on third and one out. The outfielder made the routine catch, setting up the showdown at home plate.

The runner on third sprinted home with “Pete Rose” intentions. The throw came in hard and accurate. I covered the plate in anticipation of the play–waiting for the ball while preparing for impact–and ready for the tag.

But the runner arrived just before the ball. He came in fast and hard, battering the right side of my body.

Safe!

But not for me!

My shoulder ached for the next few months and eventually healed itself without medical intervention… or so, I thought.

What I didn’t know was that the torn labrum and the eventual arthritis in my right shoulder would become my personal weather barometer for the next three decades.

But I lived with it. I found that my old injury rarely interfered with daily life or staying active. Cycling, hiking, and paddling had little effect… until I took up pickleball.

Yes, Leah and I got caught up in the sensation–3 times a week. Because we both played tennis in a past life, we quickly improved our self-assessed ranking from 2.5 to 3.0 during our first year of play.

Over time, increased ability and better competition provided a better workout, but also contributed to greater wear and tear on my right arm. It began aching and now required a visit to an orthopod.

After an x-ray, the doc’s preliminary diagnosis of bursitis warranted a steroid injection which provided relief for only a couple of days. That’s when I knew it was time for an MRI and a follow-up with the orthopod.

But not before another Monday of morning matches… which was my ultimate undoing. While playing a doubles match, I reached for an overhead slam. Upon contact, I immediately felt and heard a pop in my shoulder accompanied by a stabbing pain. I shook it off and resumed play for the next hour.

Big mistake!

The following day, I was incapacitated and in constant pain, requiring another trip to the orthopod and a second MRI.

My radiology report revealed a much more serious injury than earlier: a torn rotator cuff, bone spurs, and extreme inflammation surrounding the joint and capsule. Only arthroscopic surgery could save me now!

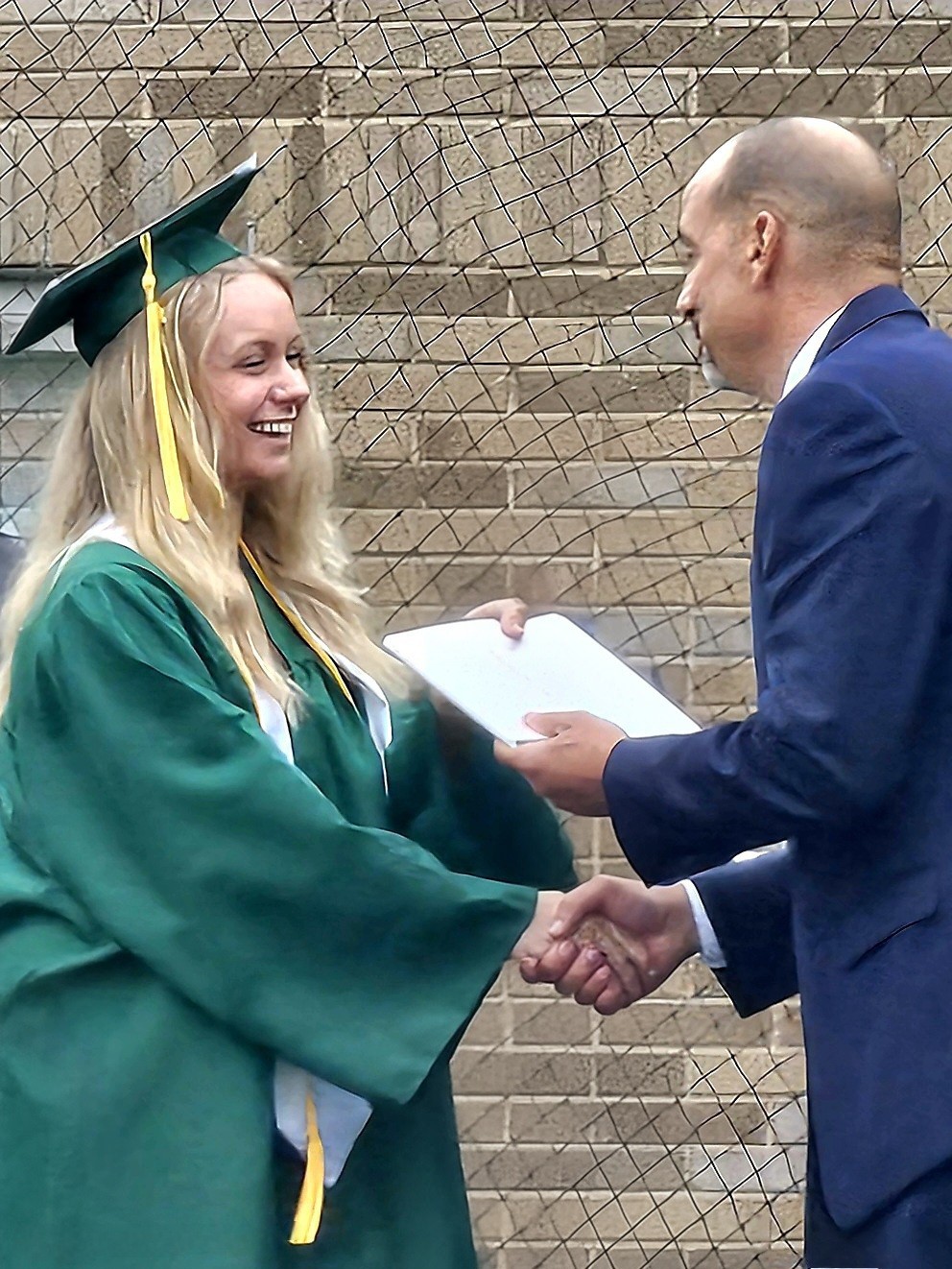

But not before a brief visit to northern New Jersey to witness Lucy, Leah’s granddaughter,

accept her diploma from Pascack Valley High School.

In addition to celebrating with family,

there was also a hike around Rockland Lake,

and a visit to the Intrepid Museum…

in NYC.

After a disastrous flight home on United (a 5-hr delay AND lost luggage), surgery was performed early next morning.

According to the surgical center, the procedure was unremarkable. My doctor repaired the rotator cuff and addressed the biceps tendinosis; he shaved the outer end of my collarbone and vacuumed the bone spurs from the AC joint; and finally, he eased the impingement by performing a subacromial decompression with acromioplasty.

After an hour in recovery, I was released to Leah, wearing a shoulder immobilizer that would soon become my arch nemesis.

Interestingly, Leah insists that despite my stupor, I was largely responsible for composing this photo.

The first couple of days were a blur–existing in and out of a drugged sleep–thanks to an oxy-cocktail and a nerve block that slowly wore off after 36 hours.

However, Hour-37 became a painful reminder that my road to recovery would be a litmus test for controlling my anxiety, because at this moment, my life feels like I’m trying to get comfortable in an economy airline seat for a 6-week flight to Normaltown.

More to follow…