What better way to escape the summer heatwave than to explore a cave. But Leah and I were literally at a subterranean crossroad of epic proportions. South Dakota’s Black Hills boasts two of the most highly respected holes in the ground anywhere in the world, and we only had time to explore one of them. Would it be Jewel Cave National Monument or Wind Cave National Park? Which cave deserved our business?

The driving distance didn’t matter since only 30 miles separated both locations. But there were other factors to consider when evaluating which cave is the better cave. When it comes to status, Wind Cave wins hands down, since it’s a National Park, and everyone knows that a National Park can’t be Trumped. On the other hand, Jewel Cave is only a National Monument, and monuments can be Zinked at any time.

We had to consider how Jewel Cave’s grand viewing rooms are endowed with a stunning collection of traditional stalactites and stalagmites, while Wind Cave holds 95% of the world’s rare boxwork formations.

As for whether size matters, Jewel Cave ranks third worldwide–four places ahead of Wind Cave at number seven in the world. However, Wind Cave has the most complicated and concentrated matrix of any cave system in the world, with new veins still being tapped.

And then there’s temperature. Jewel’s thermostat is set at 47°F, whereas Wind turns up the dial to 53°F, registering “six degrees of separation”.

And both caves offer an extremely popular assortment of tours that always sell out early on a first come first serve basis. Such a dilemma!

What’s an amateur spelunker to do?

Social media was consulted in deciding the matter, but there was no clear winner. While Jewel seemed to win the popular vote, Wind was preferred by the experts for its unique characteristics and wall structure. Yet, neither side could come together to form a coalition of consensus or compromise. And whose to say if there was voter tampering, or how many were fake views?

If travel maven and cave cognoscenti couldn’t figure it out, then how were Leah and I going to manage. We gave consideration to caves previously visited since starting out on our trip: Mammoth Cave in KY, Kickapoo Cave in TX, and Carlsbad Cavern in NM. But in the end, we settled it by tossing a buffalo head nickel. We figured, either way, we couldn’t go wrong, as long as we got there early!

And the winner was tails…

We were on our way to Wind Cave, and time was of the essence, but try explaining that to the road hogs (bison) blocking the road.

As expected, the Visitor Center parking lot was filled to capacity. I dropped Leah at the entrance crosswalk where she made a beeline for the ticket counter–beating out a Medicare couple, an escort pushing a wheelchair, and a busload of boy scouts.

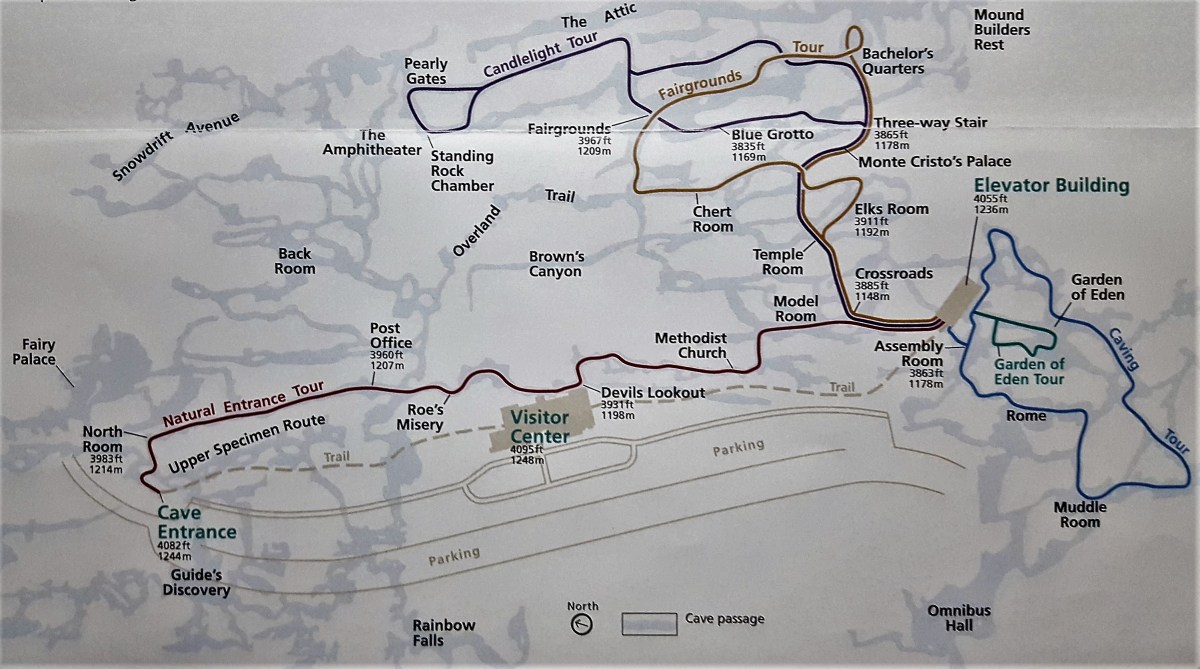

And it paid off. We scooped up the 11:20 am Natural Entrance Tour (shown in red),

which officially started at a marked clearing, featuring a hole in the ground the size of a ranger hat. Ranger Lisa demonstrated the barometric possibilities with a yellow ribbon: if pressure rose inside the cave, the ribbon would blow outward from the hole; but if cave pressure was low, the ribbon would be sucked inward–making this a cave that “breathes”.

Ranger Lisa punched her secret code into the keypad, and the steel door buzzed open, like a scene from “Get Smart”. We followed a dimly lit channel of steep stairs that snaked through a claustrophobic passage of popcorn-coated walls,

until we reached the Post Office. I can only surmise that its name comes from the butterfly of boxes stretched across the ceiling…

with the names of past generations of visitors posted inside the boxes

We followed Ranger Lisa down another set of meandering stairs along a poured concrete walkway that took Civilian Conservation Corpsmen eight years to complete, hauling inner tubes filled with sixty pounds of wet cement around their necks. We reassembled as a group at Devil’s Lookout to examine a ceiling dominated by intricate boxwork and delicate needle-like growths of calcite called frostwork.

That’s when Lisa cut power to the lights and the cave went dark. We were instructed in advance to turn off all phones and shutter all cameras. Children with glow shoes were warned to stand still or risk an extra minute of darkness away from mom or dad.

The darkness brought giggles and Halloween howls from some of the kids, but for many it was a minute to imagine what it was like to be led by Alvin McDonald on a candlelight tour during the 1890’s, when it only cost a $1.00 to crawl through the dirt.

The tour concluded in the assembly room with a brief discussion about the geologic timeline–when the cave was born between 40 to 50 million years ago as determined by sedimentary layers of rock pressurized in the cave walls.

Finally, the fastest elevator in all of South Dakota whisked us to the surface, and the tour was history.

Dear Trip Adviser, I believe that going to Wind Cave National Park was a good call, ’cause there was lots of really neat stuff on the walls and ceiling, and especially ’cause I got to pinch Leah’s ass when the lights went out.

then crashing against the brush-stroked walls of Yellowstone’s Grand Canyon.

then crashing against the brush-stroked walls of Yellowstone’s Grand Canyon.

The twisting road through the many park features and attractions carried us out to Manitou Springs, the gateway to Pikes Peak, and a pop culture village filled with hipsters, curiosity seekers, and wannabees.

The twisting road through the many park features and attractions carried us out to Manitou Springs, the gateway to Pikes Peak, and a pop culture village filled with hipsters, curiosity seekers, and wannabees.

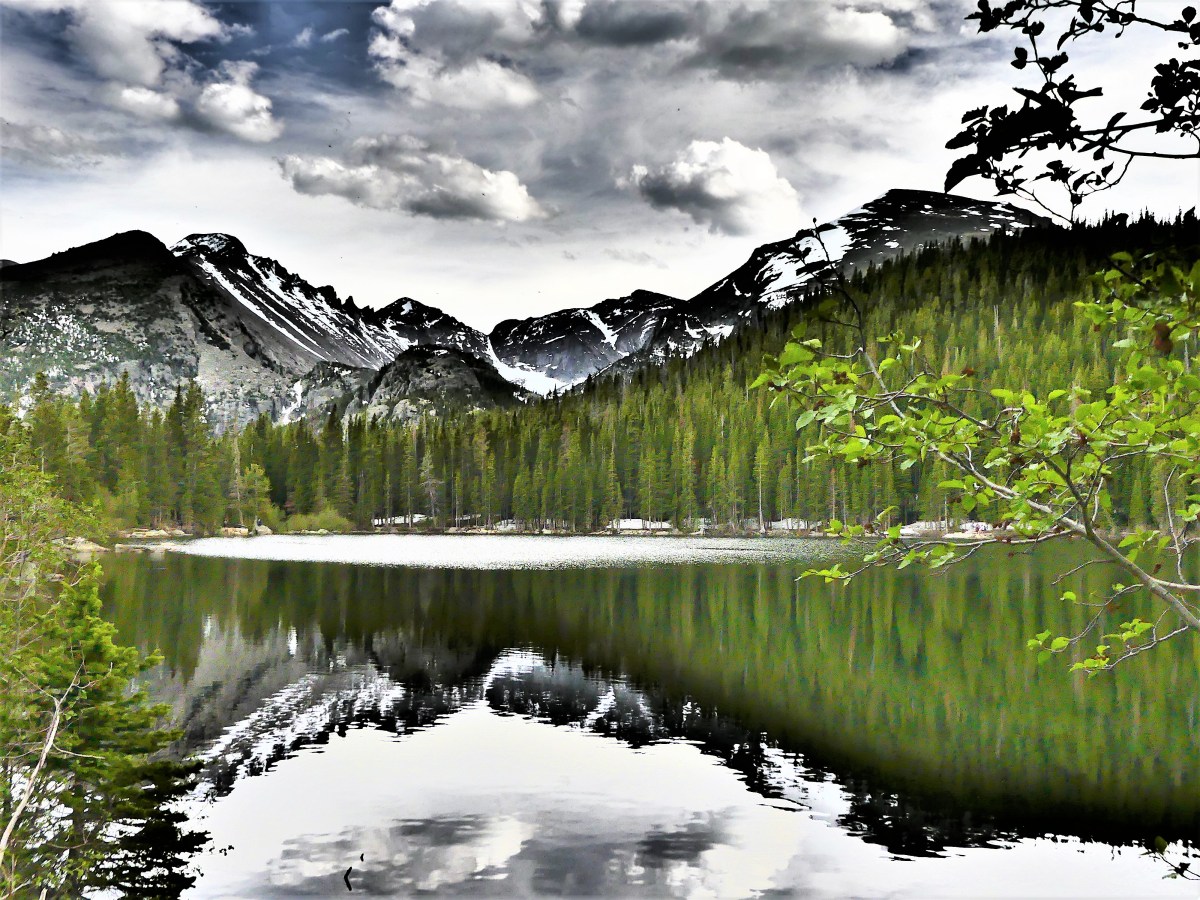

Although the views are enough to distance you from the rest of the world, the cold is enough to bring you closer together.

Although the views are enough to distance you from the rest of the world, the cold is enough to bring you closer together.

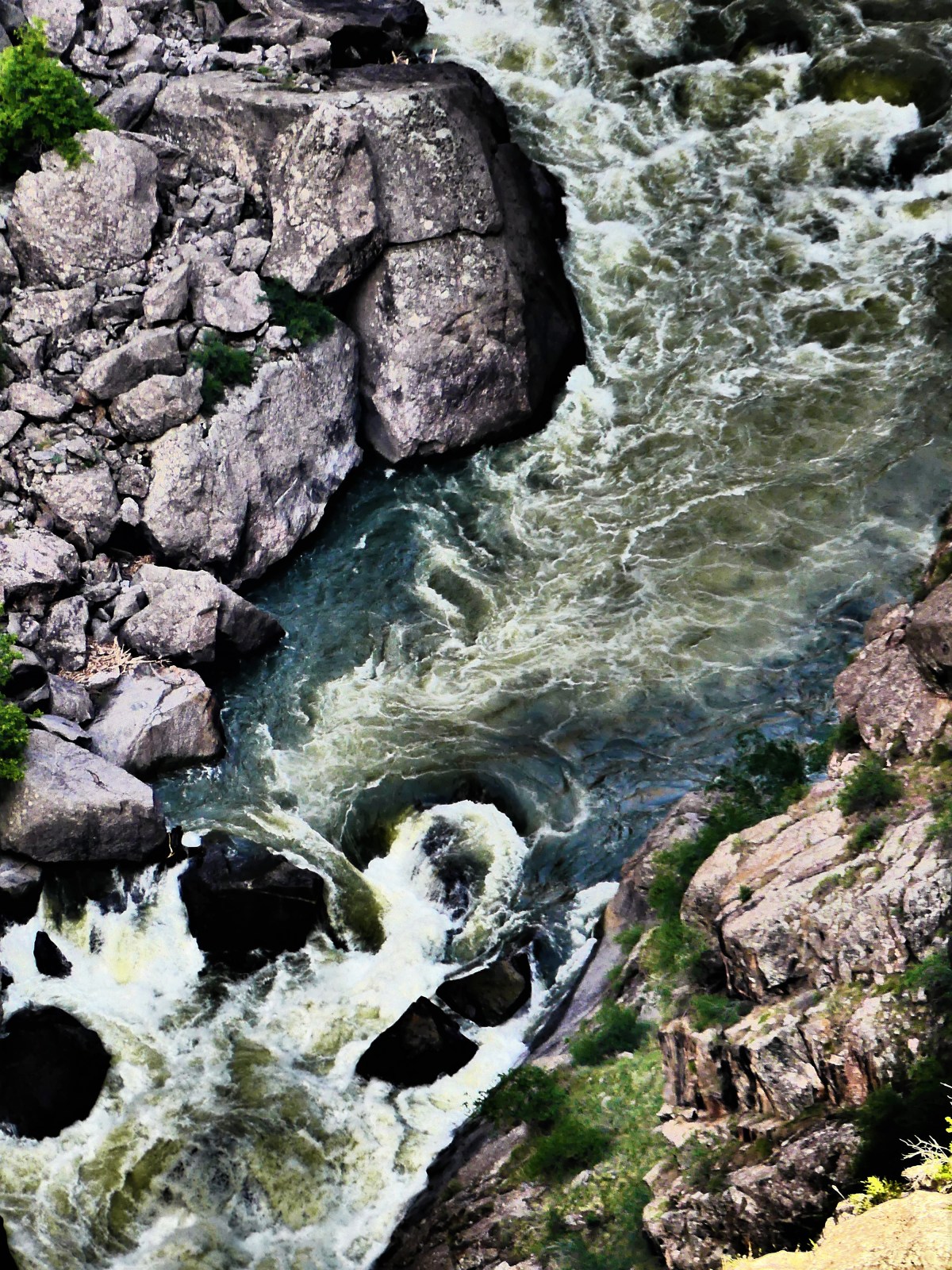

as the roar of the Gunnison River echoes against the sheer walls of gneiss and schist.

as the roar of the Gunnison River echoes against the sheer walls of gneiss and schist.

The river’s pivotal role in carving out 2 million years of metamorphic rock has resulted in canyon walls that plunge 2700 vertigo-inducing feet at Warner Point into wild water that has been rated between Class V and unnavigable.

The river’s pivotal role in carving out 2 million years of metamorphic rock has resulted in canyon walls that plunge 2700 vertigo-inducing feet at Warner Point into wild water that has been rated between Class V and unnavigable.

The view at Dragon Point showcases brilliant stripes of pink and white quartz extruded into the rock face, personifying two dragons who have symbolically fused color into a somber Precambrian edifice.

The view at Dragon Point showcases brilliant stripes of pink and white quartz extruded into the rock face, personifying two dragons who have symbolically fused color into a somber Precambrian edifice.

and focuses on an untamed water system that’s required three dams to slow the erosion of the canyon floor.

and focuses on an untamed water system that’s required three dams to slow the erosion of the canyon floor. According to Park Service statistics, left unchecked, the Gunnison River at flood stage would charge through the gorge at 12,000 cubic feet per second with 2.75 million-horse power force. Dams now provide hydroelectric energy, and have created local recreation facilities for water sports, including Blue Mesa Reservoir, Colorado’s largest body of water.

According to Park Service statistics, left unchecked, the Gunnison River at flood stage would charge through the gorge at 12,000 cubic feet per second with 2.75 million-horse power force. Dams now provide hydroelectric energy, and have created local recreation facilities for water sports, including Blue Mesa Reservoir, Colorado’s largest body of water.

sprinkle in some petroglyphs,

sprinkle in some petroglyphs,

you would have a delicious National Park named Capitol Reef that few would ever taste. And that would be the greatest crime, because this is a four-course park that satisfies all the senses, and requires at least four days to consume all it has to offer.

you would have a delicious National Park named Capitol Reef that few would ever taste. And that would be the greatest crime, because this is a four-course park that satisfies all the senses, and requires at least four days to consume all it has to offer. But we would not be detained. The truck’s high clearance and V-8 muscle was more than enough to plow through two feet of fast water, cutting a red swath through the wash, and a sending a bloody spray across my windshield and windows. The benefit of beating the waterfall gave us the road ahead to ourselves, as all the other cars were left behind in our wake.

But we would not be detained. The truck’s high clearance and V-8 muscle was more than enough to plow through two feet of fast water, cutting a red swath through the wash, and a sending a bloody spray across my windshield and windows. The benefit of beating the waterfall gave us the road ahead to ourselves, as all the other cars were left behind in our wake. and coincidentally coincided with a Sirius-XM radio broadcast of Trump announcing the American withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord. It’s hard to relay the irony of negotiating the winding narrow passage between the canyon walls while listening to Trump rationalize his decision under the guise of job losses in front of a partisan Rose Garden rally. With every fractured sentence and every tired hyperbole, the crowd would erupt with enthusiastic applause, acknowledged by Trump’s demure, “Thank you, thank you.”

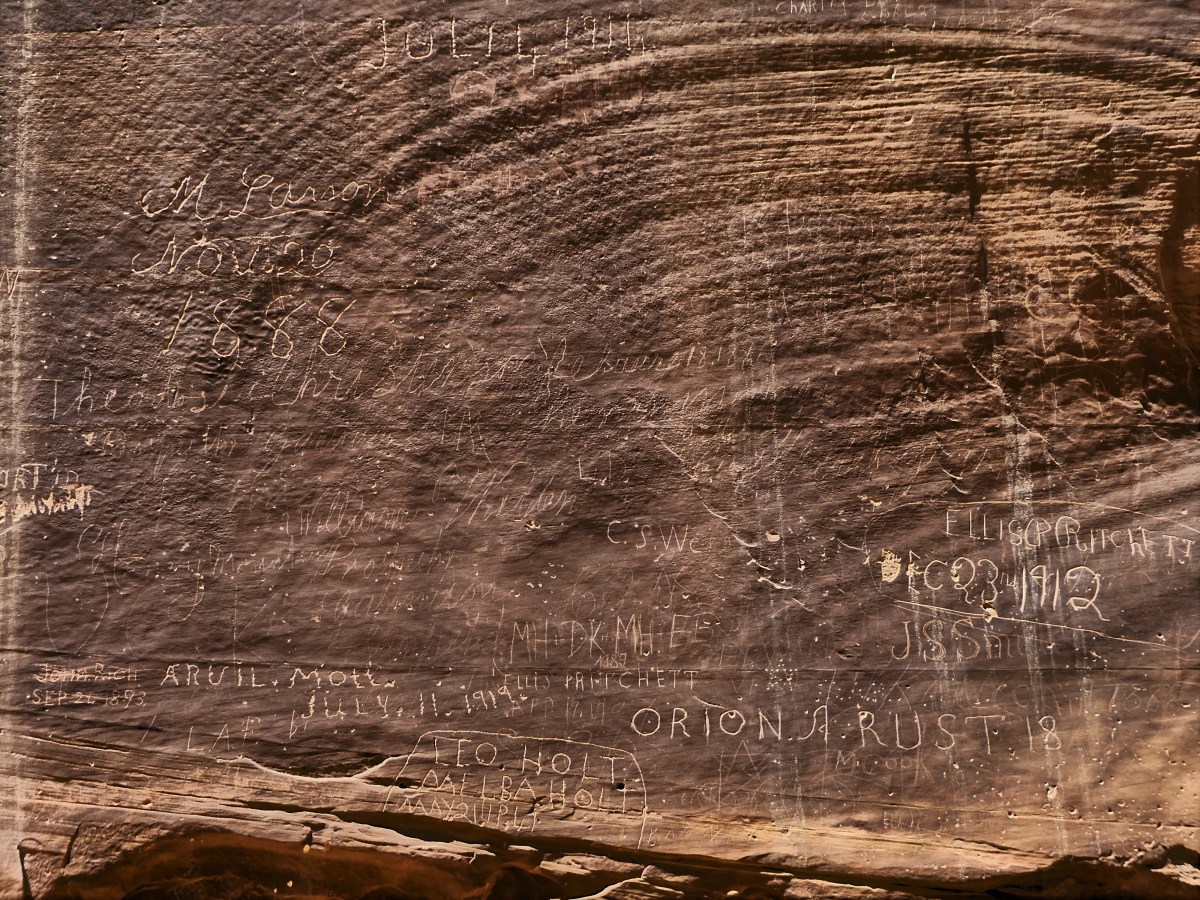

and coincidentally coincided with a Sirius-XM radio broadcast of Trump announcing the American withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord. It’s hard to relay the irony of negotiating the winding narrow passage between the canyon walls while listening to Trump rationalize his decision under the guise of job losses in front of a partisan Rose Garden rally. With every fractured sentence and every tired hyperbole, the crowd would erupt with enthusiastic applause, acknowledged by Trump’s demure, “Thank you, thank you.” tracing many generations of footsteps before us.

tracing many generations of footsteps before us. These people left us a great treasure (discounting the grafitti–more on that later) to inspire us, but also assigned us a great responsibility to preserve and protect it so that future generations may also be inspired. Our legacy as moral and ethical humans relies on it. And our future as a planet depends on it.

These people left us a great treasure (discounting the grafitti–more on that later) to inspire us, but also assigned us a great responsibility to preserve and protect it so that future generations may also be inspired. Our legacy as moral and ethical humans relies on it. And our future as a planet depends on it.

offering panoramic views of the Colorado Plateau going as far back as the Grand Canyon’s North Rim. Clear days at Bryce can offer the longest views anywhere on the planet–beyond 100 miles away, thanks to the amazing clean air quality.

offering panoramic views of the Colorado Plateau going as far back as the Grand Canyon’s North Rim. Clear days at Bryce can offer the longest views anywhere on the planet–beyond 100 miles away, thanks to the amazing clean air quality.

through the Navajo Loop Trail following the steep switchbacks…

through the Navajo Loop Trail following the steep switchbacks… to Wall Street, where enormous Douglas firs have balanced in the rift for over 750 years, like sacred totems,

to Wall Street, where enormous Douglas firs have balanced in the rift for over 750 years, like sacred totems, and views of Thor’s Hammer are something to “marvel”.

and views of Thor’s Hammer are something to “marvel”. Beyond Twin Bridges (another iconic hoodoo formation),

Beyond Twin Bridges (another iconic hoodoo formation), another series of switchbacks dropped us to the Amphitheater floor. Rather than continue the loop, we opted to cross into Queens Garden, for cake and a spot of iced tea.

another series of switchbacks dropped us to the Amphitheater floor. Rather than continue the loop, we opted to cross into Queens Garden, for cake and a spot of iced tea. standing along side the Queen’s castle…

standing along side the Queen’s castle… as Queen Victoria looked on high.

as Queen Victoria looked on high. It was a “monumental” hike out of the canyon that left us tired, but enthused by the energy surrounding us. Perhaps it was hoodoo voodoo?

It was a “monumental” hike out of the canyon that left us tired, but enthused by the energy surrounding us. Perhaps it was hoodoo voodoo? But one thing that we both agreed on… we were ravenous after spending time in this imaginary Fairyland world.

But one thing that we both agreed on… we were ravenous after spending time in this imaginary Fairyland world.

Shades of

Shades of

The road continued another 7.5 miles up and down multiple grade changes, curling in and around exposed mountain walls, and mimicking the serpentine lines of the Rio Grande, making it a driver’s delight and a passenger’s revelation. It’s little wonder that El Camino del Rio has consistently ranked as a “ten-best” scenic drive in America.

The road continued another 7.5 miles up and down multiple grade changes, curling in and around exposed mountain walls, and mimicking the serpentine lines of the Rio Grande, making it a driver’s delight and a passenger’s revelation. It’s little wonder that El Camino del Rio has consistently ranked as a “ten-best” scenic drive in America. The signage throughout the State Park suffers because of its immensity (300,000 acres) and limited resources, so having Mike as lead proved advantageous, since it would have been so easy to overshoot the trail head in favor of the surrounding vistas and roadside scenery.

The signage throughout the State Park suffers because of its immensity (300,000 acres) and limited resources, so having Mike as lead proved advantageous, since it would have been so easy to overshoot the trail head in favor of the surrounding vistas and roadside scenery. “Anything we should watch for?” I asked.

“Anything we should watch for?” I asked. While the wildlife sighting reanimated us, Leah wasn’t sufficiently satisfied.

While the wildlife sighting reanimated us, Leah wasn’t sufficiently satisfied. Uncertain of Mike’s politics, I lobbed him an ICE-breaker. “Any chance,” I subtly inquired, “we’ll have a Mexican sighting?”

Uncertain of Mike’s politics, I lobbed him an ICE-breaker. “Any chance,” I subtly inquired, “we’ll have a Mexican sighting?”

No argument from me. We worked our way further into the slot, scrambling over, around, and down water-polished rock, sometimes stopping to avoid the many tinajas–potholes of jaundiced water of undetermined depths scattered across the canyon bottom.

No argument from me. We worked our way further into the slot, scrambling over, around, and down water-polished rock, sometimes stopping to avoid the many tinajas–potholes of jaundiced water of undetermined depths scattered across the canyon bottom. After an hour on the trail we reached an impasse. At this point, the canyon walls were narrow enough to touch with both arms extended, but the tinaja before us was too deep to ford, and too wide to bypass. All we could do was turnaround and hike out.

After an hour on the trail we reached an impasse. At this point, the canyon walls were narrow enough to touch with both arms extended, but the tinaja before us was too deep to ford, and too wide to bypass. All we could do was turnaround and hike out.

Surely, there must be gators here. Why else would they post a sign, we wondered. Yet we saw no alligators. However, another hiker told us that she was told by a park ranger who had heard from another ranger that a resident gator was spotted earlier in the day crossing the road in front of our campground–the very same road where we towed our Airstream, so that should count, right?

Surely, there must be gators here. Why else would they post a sign, we wondered. Yet we saw no alligators. However, another hiker told us that she was told by a park ranger who had heard from another ranger that a resident gator was spotted earlier in the day crossing the road in front of our campground–the very same road where we towed our Airstream, so that should count, right?