Random snaps of landmarks, skylines, and curiosities captured while cruising around town. There is no particular theme or connection, but these images caught my eye, nonetheless!

Finding and reporting what's special across America

Random snaps of landmarks, skylines, and curiosities captured while cruising around town. There is no particular theme or connection, but these images caught my eye, nonetheless!

Phnom Penh and the Khmer Republic fell to the Khmer Rouge on April 17, 1975.

For the Communists, it was Liberation Day and cause for celebration.

While it marked the end of civil war, it was the beginning of one of history’s darkest chapters. Almost immediately, the Khmer Rouge ordered the exodus of the city’s 2 million inhabitants.

Khmer Rouge strongman, Pol Pot declared 1975 “Year Zero,” in his quest to build a classless agrarian utopia patterned after Maoist China, but it also marked the start of a genocide that would devastate the country, claiming over 25% of the population through forced labor, starvation and slaughter.

It started with a civil servant purge that eliminated tens of thousands of military loyalists, local police, and anyone associated with the previous government. Additional targets included academics, professionals, and “impure” ethnic minorities.

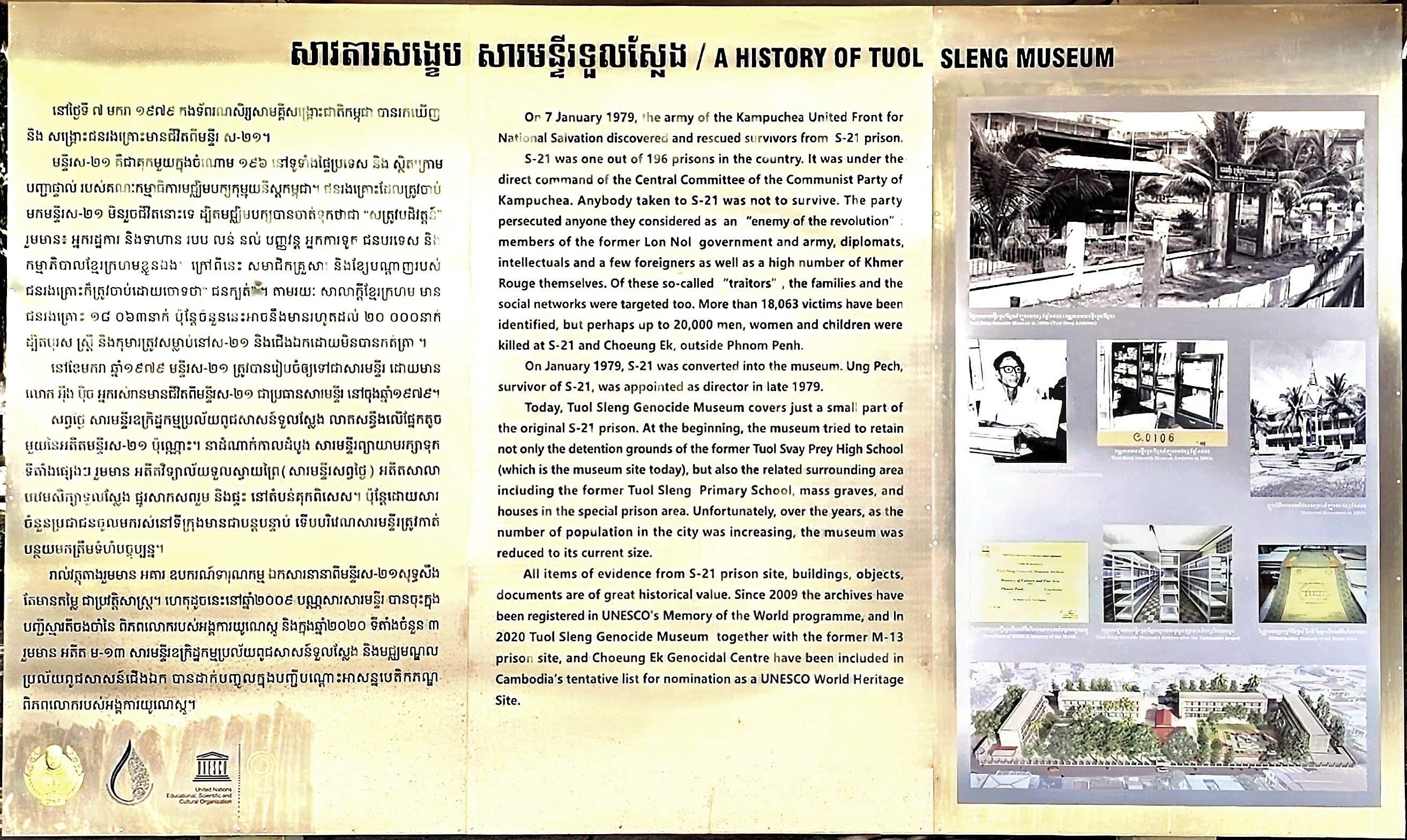

To facilitate the Khmer Rouge agenda, an education campus in Phnom Penh that housed Tuol Svay Prey High School and Tuol Sleng Primary School was commandeered and codenamed “S-21”–the nerve center of the Khmer Rouge secret police.

The survivors remember that day as the day when hope turned to horror, changing their lives forever.

For Vann Nath (tall man in the middle), the unexpected journey to Tuol Sleng began with his arrest in 1978 while working in a rice field. Before 1975, he led a normal life as a commercial artist in Battambang. The Khmer Rouge first detained him at Wat Kandal–a temple turned detention center– and accused him of violating the regime’s moral code before moving him to S-21.

Detainees arrived in handcuffs and were immediately photographed. Today, their images hang on bulletin boards as a numbing reminder of their journey into hell.

Following intake and registration, they were showered.

High-ranking cadres were imprisoned and interrogated in larger cells,

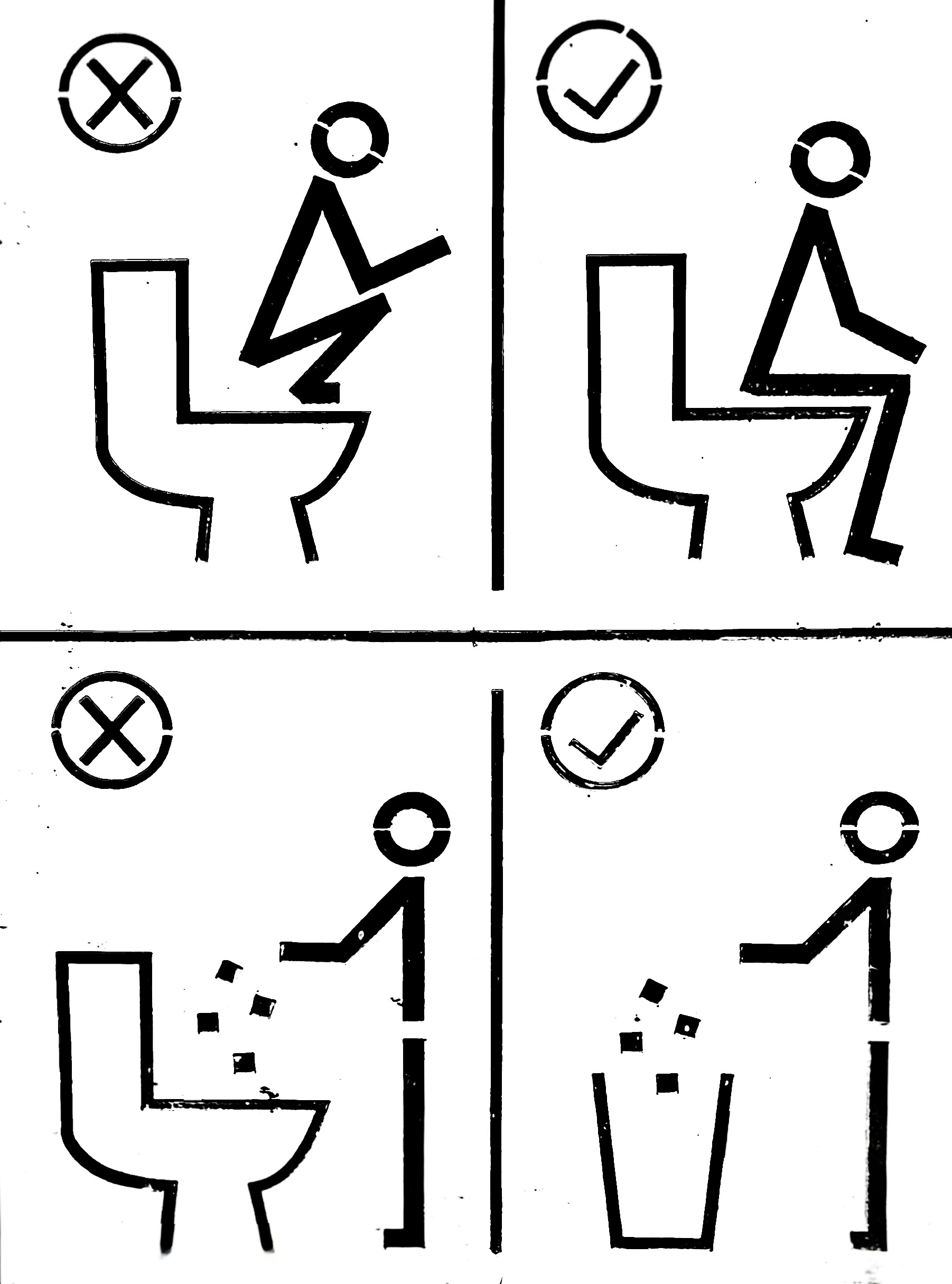

while the masses were confined to bricked-in cubbies the size of shower stalls, with ammunition boxes for toilets.

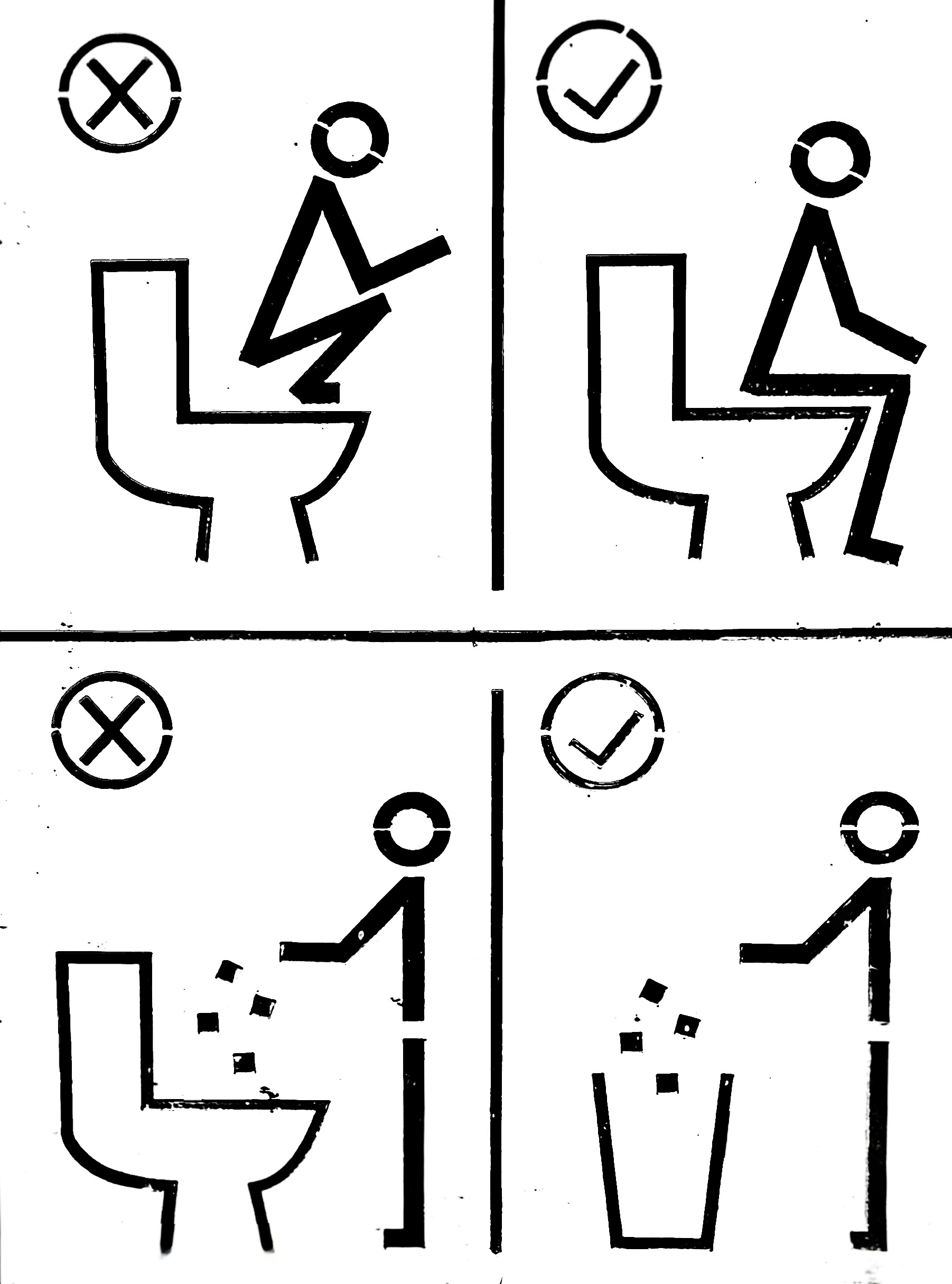

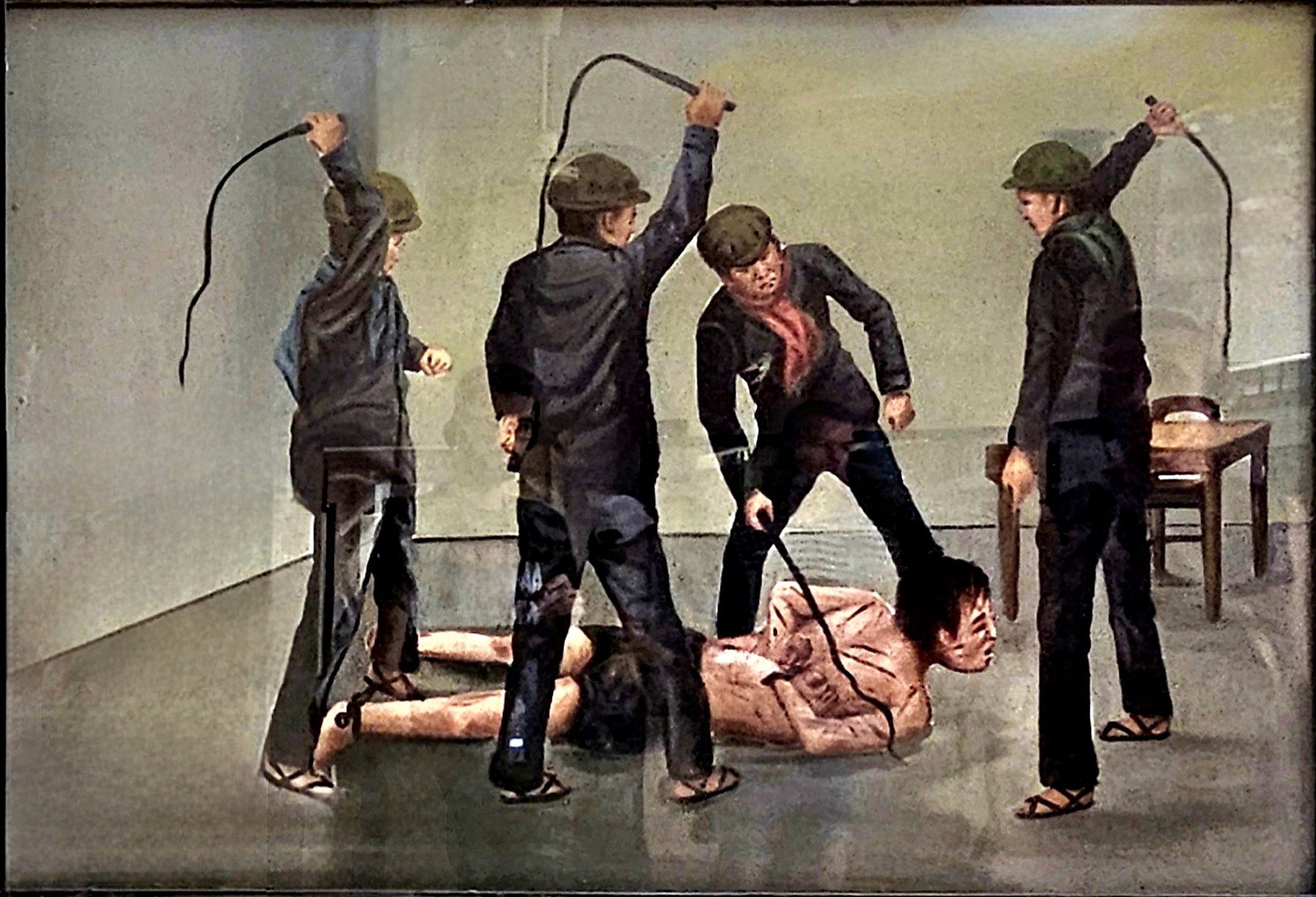

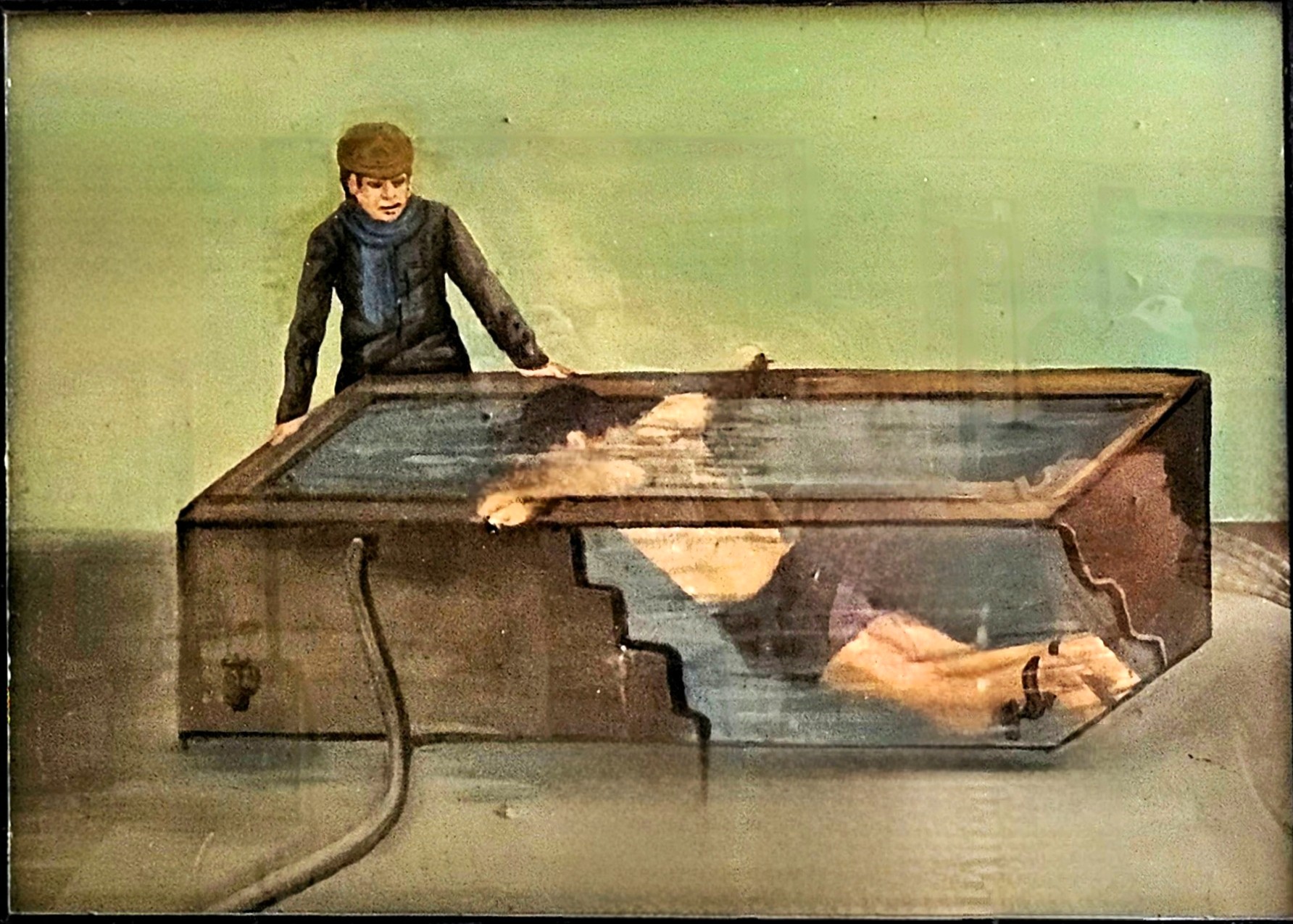

Of course, Vann was interrogated…

and tortured to extract a confession,

according to a strict code of conduct.

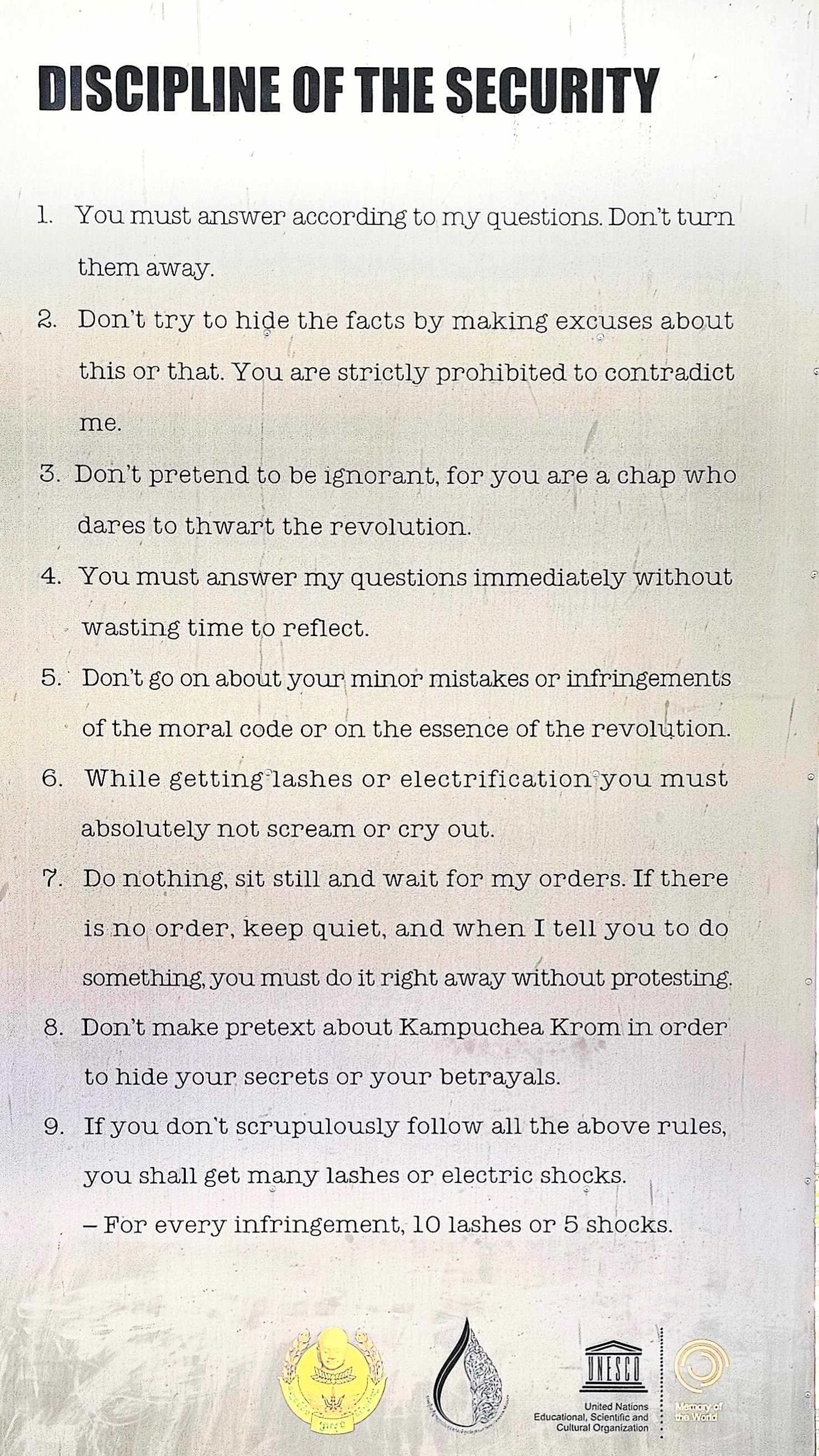

Archives from S-21 reveal that initially, Vann was to be executed, but the commandant spared him in exchange for the portraits he later painted of their supreme leader, Pol Pot.

Vann was among the handful of prisoners who narrowly escaped death by virtue of their special skills and usefulness to the regime.

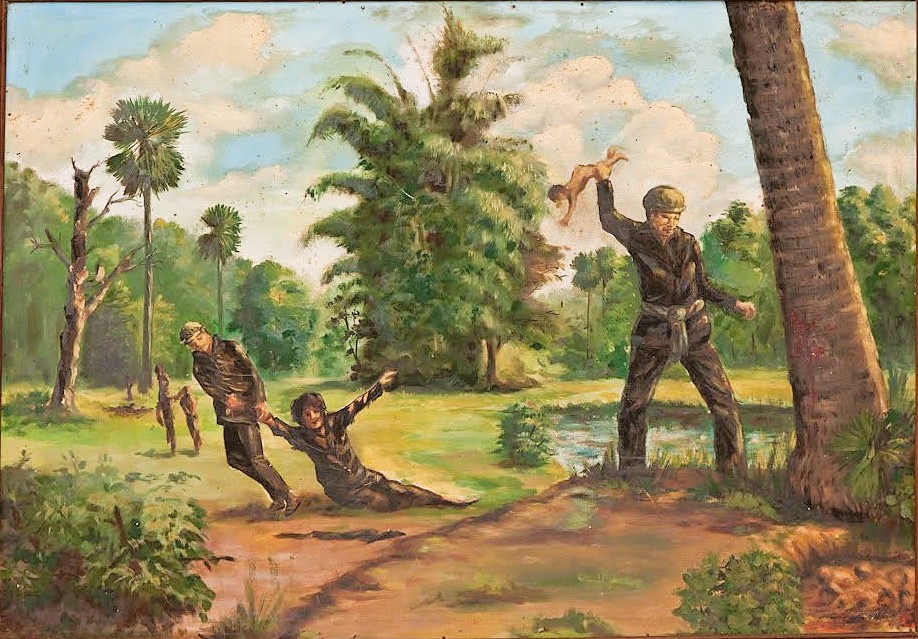

Vann’s first-person account of his misfortune was interpreted years later after his release through a series of colorful graphic depictions–on permanent display throughout the museum–that ironically brings life to the drab surroundings of prison buildings.

These vibrant illustrations vividly capture the stark contrast between the bleak memories of confinement and the essence of freedom, allowing us to connect emotionally with Vann’s experiences.

The cracked walls reflect the forgotten whispers of hope and despair, transforming the narrative into an immersive journey that transcends time and pain.

The art not only serves as a commentary on the injustices faced but also inspires conversations about redemption, resilience, and the profound impact of creativity in the face of adversity.

Chum Mey is another survivor who’s grateful for his mechanical skills. By fixing the typewriters used to record the forced confessions of fellow prisoners, Chum Mey managed to escape a death sentence, but not the torture. He sits at the edge of the museum courtyard, eager to recount his story in horrific detail. “I come every day to tell the world the truth about the Tuol Sleng prison… so that none of these crimes are ever repeated anywhere in the world.”

Our group was also moved by our off-site exchange with Norng Chan Phal, who delivered his oral history through an interpreter. He was 9-years old in 1978, when his world was turned upside down. His father was arrested and executed at Tuol Sleng. Months later, the Khmer Rouge returned for the rest of his family. He recalled his mother’s torture and disappearance, and how he and his brother hid under piles of dirty laundry to escape retreating guards after S-21 was liberated.

Even now, the burden of remembering brings on sudden sadness.

All three survivors later testified against senior leadership before the UN-backed Khmer Rouge genocide tribunal, which led to their convictions.

Tuol Sleng was liberated by the Vietnamese Army in January 1979, and reopened the following year as a museum.

Cambodia’s willingness to confront its past is only one part of the healing process. Youk Chhang, director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) states, “Post-conflict nations must redefine themselves and actively commit to a future without violence, atrocity crimes and genocide.”

At first glance, Choeung EK is an inviting greenspace on the edge of Phnom Penh,

with flowering trees,

and a peaceful lotus pond stocked with ancient koi.

Located 12 km from City Center, it’s conveniently adjacent to AEON Mean Chey, the city’s trendiest and largest all-purpose shopping center and fashion mall targeting Cambodia’s rising middle class.

Although, from my perspective, the only fashion that’s display-worthy is a collection of fabric remnants protected in a glass box…

once worn by 20,000 prisoners whose remains continue to float to the surface during every rainy season.

On closer inspection, the heritage trees throughout the grounds were once used as tools of brutality by agents of Khmer Rouge: from towers of dissonance,

to hardwood battering pillars.

Over the years, visitors to Choeung EK Genocidal Center have rebranded this tree as an ad hoc totem to memorialize the fate of thousands of children whose skulls were bashed against it.

Nearby, a stunning Buddhist stupa rises from the epicenter of the killing field…

housing thousands of adult skulls recovered during a site excavation in the 1980’s.

Between 1995 and 2007, the Documentation Center of Cambodia undertook the most challenging and disheartening task of mapping and documenting Cambodia’s killing fields. Through thousands of interviews and field investigations, DC-Cam identified 19,733 mass graves and 196 prisons that operated during the Democratic Kampuchea (DK) regime.

Choeung EK’s conversion from orchard to reeducation center…

served as a lethal gateway for every soul imprisoned at the notorious Tuol Sleng Detention Center.

All day long, trucks rolled into S-21, herding political enemies into primitive barracks,

where they ultimately met their untimely fate through horrific violence.

In 5 years, an estimated 2 million Cambodians (men, women, children, and infants) were murdered by Khmer Rouge,

accounting for 25% of the nation’s population.

Choeung EK reopened as a historical museum and learning center on January 7, 1989, with a mission to acknowledge the historical atrocities that occurred, and to remind us that violence against each other can have devastating consequences.

Its exhibits, memorials, and curated educational programs engage visitors in meaningful conversations about human rights and reconciliation.

Cambodians will soon commemorate their loss with a National Day of Remembrance. Every May 20th, students take part in an annual ritual–reenacting the crimes of Khmer Rouge guerillas–that still haunt Cambodian people deep to the bone.

On that day and every day, we pray for healing and understanding, and the realization that confronting past acts of inhumanity will inform and guide the well-being of future generations.

While sifting through hundreds of photographs taken during a recent tour of Southeast Asia (see past posts), I weeded out a wave of watercraft shots, and thought a maritime montage of nautical notions would make the perfect post.

During our visit to Kanchanaburi, Leah and I enjoyed time on the River Kwai in a traditional long-boat…

giving us splendid views along the water,

and a glimpse of river-lounging for well-heeled tourists:

But it wasn’t until we returned to Bangkok’s Chao Phraya that we gained a greater appreciation of the river’s transportation network:

of river buses, cross-river ferries, water taxis, and sunset party boats.

On another occasion, we boarded a long tail to cruise upriver on the Chao Phraya,

taking in the sites of the ancient capital of Ayutthaya…

along the waterfront.

But the mighty Mekong is Southeast Asia’s “Mother of all Rivers” and most significant waterway. It winds its way from the Tibetan Plains to the South China Sea, running through Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam, making it the region’s longest river at nearly 3,000 miles.

The Mekong is also the most productive river on the planet–boasting the world’s largest inland fishery–

which accounts for up to 25% of the global freshwater catch while providing livelihoods for 90 million people,

and supporting 54,000 sq mi of rice crops.

While touring upper Chiang Rai, Leah and I were hypnotized watching the confluence of Myanmar’s Roak River flowing into the Mekong–

separating Thailand and Laos to form the Golden Triangle.

But it wasn’t until our visit to Luang Prabang, Laos that we caught a second look at the Mekong–this time during golden hour–

which set the stage for our cruise the following day on a traditional wooden boat.

We motored slowly upriver to where the Mekong meets the Nam Ou River at Ban Pak Ou,

and disembarked directly across from the village…

to explore the Pak Ou Caves–Tham Ting and Tham Theung–located on the west bank of the Mekong River.

The first Lao people arrived at Ban Pak Ou from South China during the 8th century. They brought a strong belief in spirits and a profound respect for all things nature. It was an animistic religion known as Ban Phi.

The villagers believed that the caves were enchanted with river spirits, and they performed periodic blood sacrifices for prosperity and protection, but by the 16th century, Buddhism had been adopted by the royal families of Lao, who offered their patronage until the last days of the monarchy in 1975.

While Buddhism remains a unifying feature of Lao culture, animistic rituals continue to thrive and have been seamlessly integrated into Buddhist ceremonies, allowing Shamans and monks to symbiotically tend to the spiritual needs of their worshippers.

These days, the caves are a well-known repository for over 4,000 miniature Buddha sculptures, mostly old or disfigured impressions dating from the 18th century.

We were reacquainted with the Mekong during our stay in Phnom Penh, where we enjoyed a delightful sunset cruise on the river,

with all the beer we wanted!

The ever-shifting city skyline…

stands in stark contrast with Akreiy Ksatr Village on the opposite bank.

But a new ferry station supports continued growth along the river in every sector,

making Cambodia an emerging economic engine among ASEAN nations.

Lastly, during our visit to Vietnam, Leah and I traversed the Mekong Delta on a chartered riverboat.

As we navigated inside a shallow tributary, my mind quickly turned to Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness,” with haunting visions of Marlow’s journey on the Congo River.

Initially, our captain wondered if the incoming tide would lift our boat over the mud, unlike other sidelined sailors,

as we managed to crawl through the middle of the passage at low tide.

Eventually, we exchanged our boat for an excursion by sampan,

until we reached our next location,

where Siamese crocodiles are on the menu and not on the Mekong, thankfully!

There were many other water activities throughout our tour, yet nothing prepared us for a day on Tonlé Sap, where we observed Cambodians living on the water, full-time.

But that’s a story for another time…