With so much attention being paid to the over-crowded conditions at National Parks this year, Leah and I were optimistic that Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP) would allow us some breathing room—despite a doomsday article recently published by Denver Post that boasted a 21% increase in visitor attendance at RMNP over the same month last year (Denver Post). According to the NPS, more than 1 million people will make RMNP their vacation destination in the next six weeks and that does not bode well for the visitor who comes to enjoy the park.

Apparently, when Trump announced a federal hiring freeze one week after taking office, the park was unable to move forward with seasonal hires, leaving the Park Service unprepared to staff its most popular and profitable parks. Additionally, there was no budget allowance for background checks and bonding of future employees, which has translated into longer lines at Park Service admissions, and fewer transactions at Park Service Conservancy Nature Stores. Penny-wise, pound-foolish economics!

We arrived in line at 1pm on Monday. After half-an-hour, we crossed the threshold into RMNP. Signs were posted along the way announcing full occupancy at all campgrounds. I felt fortunate snagging a camp-site for three nights at Glacier Basin—a no-services facility—through the NPS reservations web-site over six months ago.

I produced my Senior Pass credentials to the ranger at the gatehouse, and received an obligatory park map, but not a newspaper, because the official newspaper of RMNP had run out before noon. The newspapers are a vital resource to the park’s success, given the hands-on information that visitors rely on when planning their stay, notwithstanding: safety protocols, hiking trails, shuttle bus schedules, ranger-led programs, road and trail conditions, and visitor center(s) hours of operation.

After unhitching the trailer, Leah and I elected to tour the north side of the park, following the Trail Ridge Road to the Alpine Visitor Center,

and past the highest point of any NPS road (12183 ft.).

Several look-outs along the way provided ample opportunities to be blown about by sustained winds of 50 mph, admire wide-open views of nearby mountain ranges in the blistering cold, and escape from the occasional driver who negotiates a hairpin turn while pointing a camera outside his window.

With such a high number of drivers who suffer from altitude stupidity, it’s a wonder there aren’t more accidents like the one we came across that closed the road for an hour until a tow-truck arrived to cart away the collision. It’s also a special breed of driver who comes to the park and thinks it okay to stop in the middle of the road to observe a crowd watching something off the side of the road.

Sadly, it’s probably the same driver who lollygags at 18 mph, when all the vehicles trailing behind are aching to achieve the 35 mph speed limit. It’s as if people have come to the park to practice their driving, turning the roads into a fright of passage.

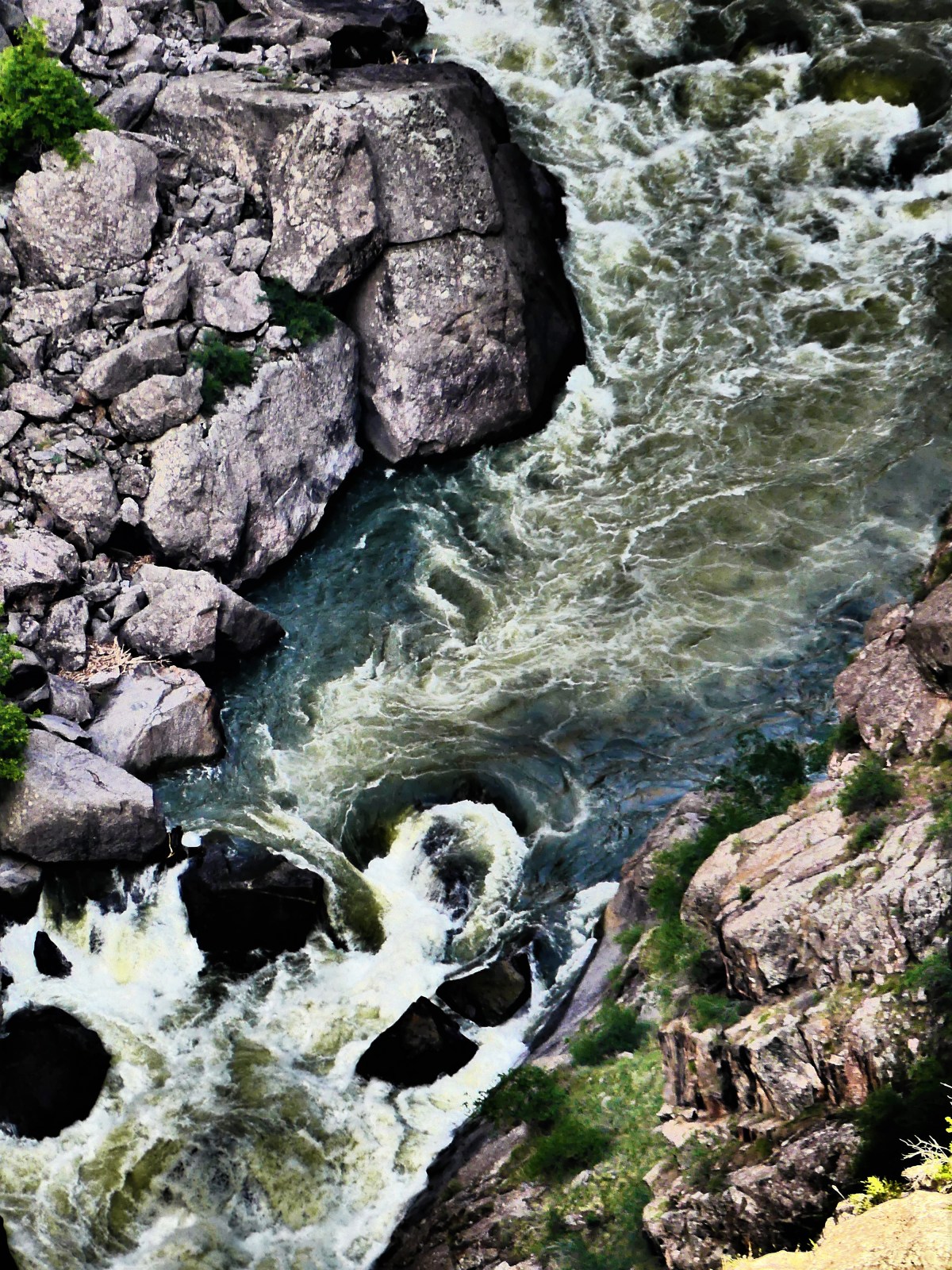

While it was difficult to completely avoid the road toads, Leah and I managed to steer clear of much the traffic tie-ups by exploring more remote regions of the park during our three-day visit. One 7-mile hike on the edge of Grand Lake took us to the top of Cascade Falls,

where so much run-off from late snow had produced a torrent of moving water.

Drainage from the Ptargiman Mountain was becoming an issue, so a crew was dispatched to redirect the spill over from the falls.

The next day, a 5-mile hike off the Moraine Park spur led us to Cub Lake in the shadow of Steep Mountain.

Considered an easy hike by the trail guide, Leah was unconvinced by the steep rocky incline to the gorge—narrow and muddy, and shared by horses—which led to lots of side-stepping.

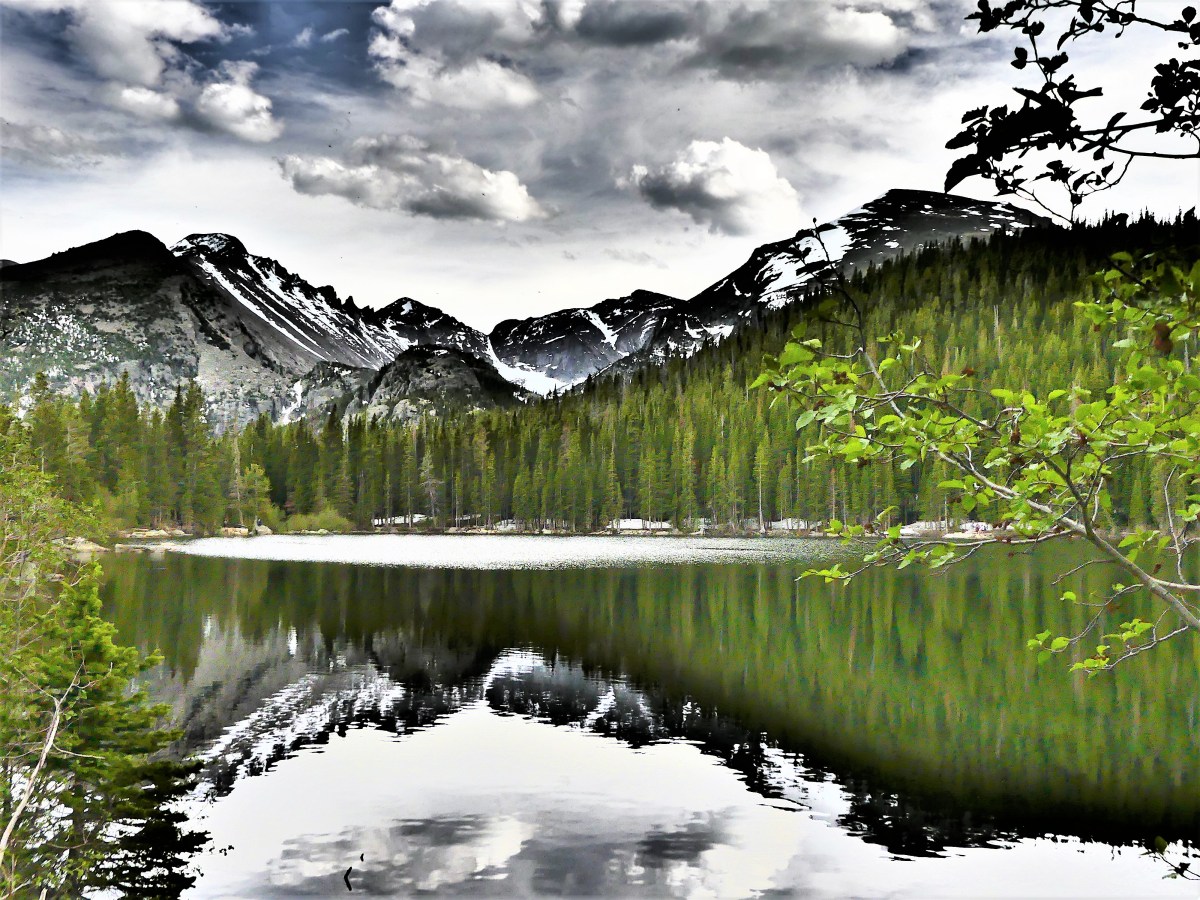

Not to be deterred, Leah would lobby for a label that was more suitable. After following the half-mile loop around Bear Lake, one of the park’s most popular subalpine locales–distinguished by its late thaw,

and smooth-as-glass lake surface–

Leah stopped to ask a ranger’s opinion of the Cub Lake Trail. To Leah’s delight, the ranger agreed that the hike should be upgraded from easy to moderate, but only because of its duration.

The thin air and jaw-dropping views of mountain peaks, canyons, snowfields, lakes, meadows, falls and forests left us breathless. But we came for the animals as well. We waited patiently for nearly an hour at Sheep Lake with the hope that the park’s bighorn sheep and their lambs might descend from the mountain to graze and lick mud in the meadow below. The timing was right—no coyotes were spotted at the pond—but the sheep had other ideas, and stayed where they were.

But there was no shortage of chipmunks, squirrels and marmots.

RMNP is a delicate ecosystem that has been managed since 1915. With so many visitors eager to pilgrimage to the park, the importance of preservation and land stewardship along with proper funding will drive the next one hundred years, provided Sunday drivers stay off the roads.

as the roar of the Gunnison River echoes against the sheer walls of gneiss and schist.

as the roar of the Gunnison River echoes against the sheer walls of gneiss and schist.

The river’s pivotal role in carving out 2 million years of metamorphic rock has resulted in canyon walls that plunge 2700 vertigo-inducing feet at Warner Point into wild water that has been rated between Class V and unnavigable.

The river’s pivotal role in carving out 2 million years of metamorphic rock has resulted in canyon walls that plunge 2700 vertigo-inducing feet at Warner Point into wild water that has been rated between Class V and unnavigable.

The view at Dragon Point showcases brilliant stripes of pink and white quartz extruded into the rock face, personifying two dragons who have symbolically fused color into a somber Precambrian edifice.

The view at Dragon Point showcases brilliant stripes of pink and white quartz extruded into the rock face, personifying two dragons who have symbolically fused color into a somber Precambrian edifice.

and focuses on an untamed water system that’s required three dams to slow the erosion of the canyon floor.

and focuses on an untamed water system that’s required three dams to slow the erosion of the canyon floor. According to Park Service statistics, left unchecked, the Gunnison River at flood stage would charge through the gorge at 12,000 cubic feet per second with 2.75 million-horse power force. Dams now provide hydroelectric energy, and have created local recreation facilities for water sports, including Blue Mesa Reservoir, Colorado’s largest body of water.

According to Park Service statistics, left unchecked, the Gunnison River at flood stage would charge through the gorge at 12,000 cubic feet per second with 2.75 million-horse power force. Dams now provide hydroelectric energy, and have created local recreation facilities for water sports, including Blue Mesa Reservoir, Colorado’s largest body of water.

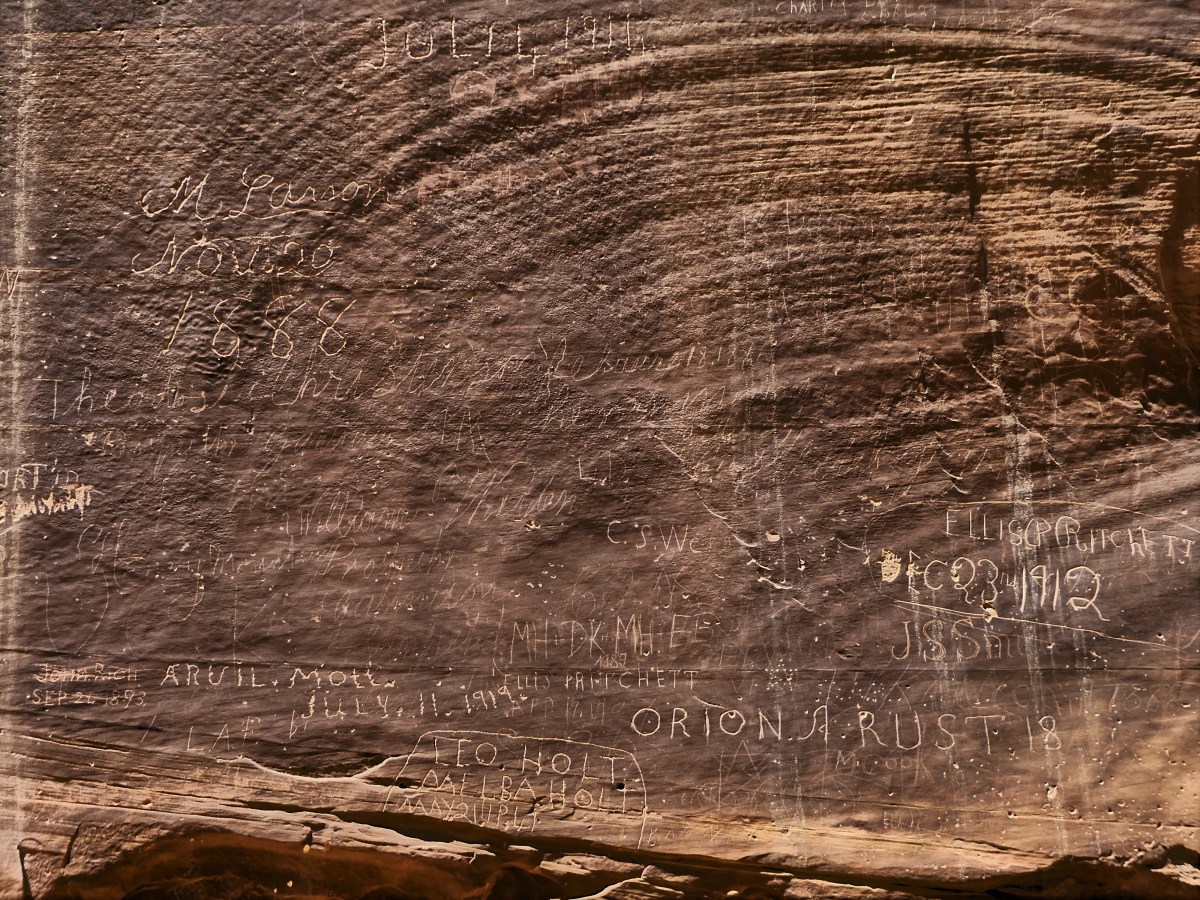

sprinkle in some petroglyphs,

sprinkle in some petroglyphs,

you would have a delicious National Park named Capitol Reef that few would ever taste. And that would be the greatest crime, because this is a four-course park that satisfies all the senses, and requires at least four days to consume all it has to offer.

you would have a delicious National Park named Capitol Reef that few would ever taste. And that would be the greatest crime, because this is a four-course park that satisfies all the senses, and requires at least four days to consume all it has to offer. But we would not be detained. The truck’s high clearance and V-8 muscle was more than enough to plow through two feet of fast water, cutting a red swath through the wash, and a sending a bloody spray across my windshield and windows. The benefit of beating the waterfall gave us the road ahead to ourselves, as all the other cars were left behind in our wake.

But we would not be detained. The truck’s high clearance and V-8 muscle was more than enough to plow through two feet of fast water, cutting a red swath through the wash, and a sending a bloody spray across my windshield and windows. The benefit of beating the waterfall gave us the road ahead to ourselves, as all the other cars were left behind in our wake. and coincidentally coincided with a Sirius-XM radio broadcast of Trump announcing the American withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord. It’s hard to relay the irony of negotiating the winding narrow passage between the canyon walls while listening to Trump rationalize his decision under the guise of job losses in front of a partisan Rose Garden rally. With every fractured sentence and every tired hyperbole, the crowd would erupt with enthusiastic applause, acknowledged by Trump’s demure, “Thank you, thank you.”

and coincidentally coincided with a Sirius-XM radio broadcast of Trump announcing the American withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord. It’s hard to relay the irony of negotiating the winding narrow passage between the canyon walls while listening to Trump rationalize his decision under the guise of job losses in front of a partisan Rose Garden rally. With every fractured sentence and every tired hyperbole, the crowd would erupt with enthusiastic applause, acknowledged by Trump’s demure, “Thank you, thank you.” tracing many generations of footsteps before us.

tracing many generations of footsteps before us. These people left us a great treasure (discounting the grafitti–more on that later) to inspire us, but also assigned us a great responsibility to preserve and protect it so that future generations may also be inspired. Our legacy as moral and ethical humans relies on it. And our future as a planet depends on it.

These people left us a great treasure (discounting the grafitti–more on that later) to inspire us, but also assigned us a great responsibility to preserve and protect it so that future generations may also be inspired. Our legacy as moral and ethical humans relies on it. And our future as a planet depends on it.

offering panoramic views of the Colorado Plateau going as far back as the Grand Canyon’s North Rim. Clear days at Bryce can offer the longest views anywhere on the planet–beyond 100 miles away, thanks to the amazing clean air quality.

offering panoramic views of the Colorado Plateau going as far back as the Grand Canyon’s North Rim. Clear days at Bryce can offer the longest views anywhere on the planet–beyond 100 miles away, thanks to the amazing clean air quality.

through the Navajo Loop Trail following the steep switchbacks…

through the Navajo Loop Trail following the steep switchbacks… to Wall Street, where enormous Douglas firs have balanced in the rift for over 750 years, like sacred totems,

to Wall Street, where enormous Douglas firs have balanced in the rift for over 750 years, like sacred totems, and views of Thor’s Hammer are something to “marvel”.

and views of Thor’s Hammer are something to “marvel”. Beyond Twin Bridges (another iconic hoodoo formation),

Beyond Twin Bridges (another iconic hoodoo formation), another series of switchbacks dropped us to the Amphitheater floor. Rather than continue the loop, we opted to cross into Queens Garden, for cake and a spot of iced tea.

another series of switchbacks dropped us to the Amphitheater floor. Rather than continue the loop, we opted to cross into Queens Garden, for cake and a spot of iced tea. standing along side the Queen’s castle…

standing along side the Queen’s castle… as Queen Victoria looked on high.

as Queen Victoria looked on high. It was a “monumental” hike out of the canyon that left us tired, but enthused by the energy surrounding us. Perhaps it was hoodoo voodoo?

It was a “monumental” hike out of the canyon that left us tired, but enthused by the energy surrounding us. Perhaps it was hoodoo voodoo? But one thing that we both agreed on… we were ravenous after spending time in this imaginary Fairyland world.

But one thing that we both agreed on… we were ravenous after spending time in this imaginary Fairyland world.

Shades of

Shades of

as we cross several dry river beds…

as we cross several dry river beds… along the arroyo to Pratt Cabin, a Depression-era structure built entirely of stone.

along the arroyo to Pratt Cabin, a Depression-era structure built entirely of stone. Rocking chairs under a cool porch provide perfect respite from the simmering sun.

Rocking chairs under a cool porch provide perfect respite from the simmering sun.

The road continued another 7.5 miles up and down multiple grade changes, curling in and around exposed mountain walls, and mimicking the serpentine lines of the Rio Grande, making it a driver’s delight and a passenger’s revelation. It’s little wonder that El Camino del Rio has consistently ranked as a “ten-best” scenic drive in America.

The road continued another 7.5 miles up and down multiple grade changes, curling in and around exposed mountain walls, and mimicking the serpentine lines of the Rio Grande, making it a driver’s delight and a passenger’s revelation. It’s little wonder that El Camino del Rio has consistently ranked as a “ten-best” scenic drive in America. The signage throughout the State Park suffers because of its immensity (300,000 acres) and limited resources, so having Mike as lead proved advantageous, since it would have been so easy to overshoot the trail head in favor of the surrounding vistas and roadside scenery.

The signage throughout the State Park suffers because of its immensity (300,000 acres) and limited resources, so having Mike as lead proved advantageous, since it would have been so easy to overshoot the trail head in favor of the surrounding vistas and roadside scenery. “Anything we should watch for?” I asked.

“Anything we should watch for?” I asked. While the wildlife sighting reanimated us, Leah wasn’t sufficiently satisfied.

While the wildlife sighting reanimated us, Leah wasn’t sufficiently satisfied. Uncertain of Mike’s politics, I lobbed him an ICE-breaker. “Any chance,” I subtly inquired, “we’ll have a Mexican sighting?”

Uncertain of Mike’s politics, I lobbed him an ICE-breaker. “Any chance,” I subtly inquired, “we’ll have a Mexican sighting?”

No argument from me. We worked our way further into the slot, scrambling over, around, and down water-polished rock, sometimes stopping to avoid the many tinajas–potholes of jaundiced water of undetermined depths scattered across the canyon bottom.

No argument from me. We worked our way further into the slot, scrambling over, around, and down water-polished rock, sometimes stopping to avoid the many tinajas–potholes of jaundiced water of undetermined depths scattered across the canyon bottom. After an hour on the trail we reached an impasse. At this point, the canyon walls were narrow enough to touch with both arms extended, but the tinaja before us was too deep to ford, and too wide to bypass. All we could do was turnaround and hike out.

After an hour on the trail we reached an impasse. At this point, the canyon walls were narrow enough to touch with both arms extended, but the tinaja before us was too deep to ford, and too wide to bypass. All we could do was turnaround and hike out.

Surely, there must be gators here. Why else would they post a sign, we wondered. Yet we saw no alligators. However, another hiker told us that she was told by a park ranger who had heard from another ranger that a resident gator was spotted earlier in the day crossing the road in front of our campground–the very same road where we towed our Airstream, so that should count, right?

Surely, there must be gators here. Why else would they post a sign, we wondered. Yet we saw no alligators. However, another hiker told us that she was told by a park ranger who had heard from another ranger that a resident gator was spotted earlier in the day crossing the road in front of our campground–the very same road where we towed our Airstream, so that should count, right?