In ancient times, the Nile split the imperial city of Thebes in two parts:

On the east bank, a fertile garden where 80,000 Egyptians lived and worked, called “City of the Living;”

and along the west bank, Egyptian royalty huddled with their architects and priests to select the best nest for rest in “City of the Dead.”

Occasionally, it was a family affair, with namesake mummies networking in the same vicinity–no doubt, making it easier to pay respects on Pharaohs Day.

Unlike Giza, the only thing resembling a pyramid in the Valley of the Kings is Al Qurn, the highest peak in the Theban Hills at 420 meters.

Perhaps this gave the pharaohs some ancestral comfort, knowing their final journey to eternity had topographical similarities.

At last count, international expeditions have excavated 65 crypts concentrated within the Valley of the Kings and Queens, with only 11 tombs available for viewing.

But the most remarkable thing about this vast necropolis is what’s waiting to be discovered. Hardly a day goes by without hearing of a new discovery from the dozens of white “dig” tents that dot Luxor and Giza.

Easily, the most famous discovery came from British archaeologist, Howard Carter,

whose remarkable discovery of King Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922 created a global sensation.

But seeing is believing.

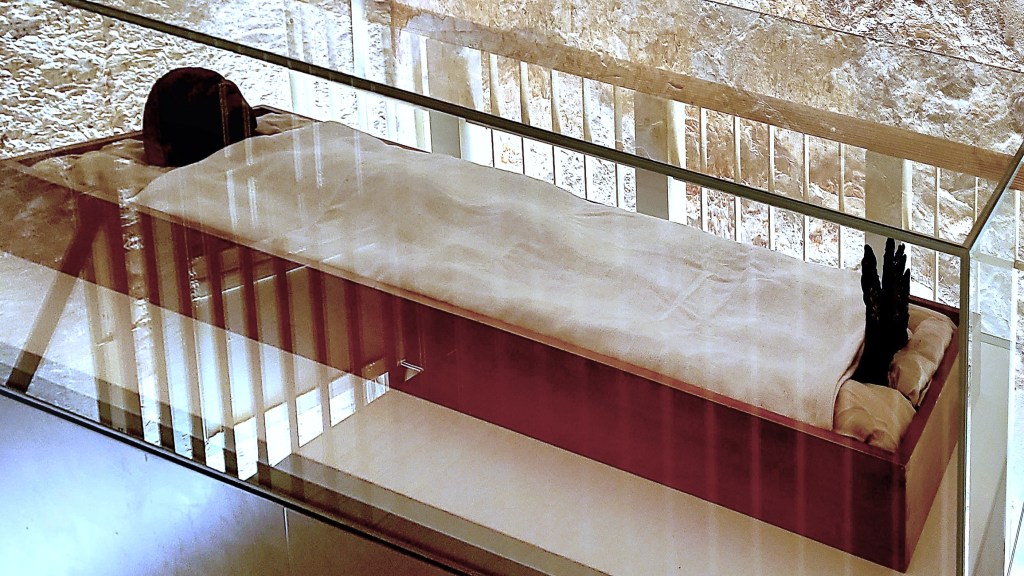

Viewing the tomb requires a special ticket, and admission is limited.

While the tomb’s treasures have been removed, (see Egyptian Museum Mania),

the mummy and first sarcophagus remain intact.

Equally impressive is the remote Temple of Deir el-Bahri (KV22), anchored to the rockface below Al Qurn.

It was commissioned by Hatshepsut, who broke the aristocratic glass ceiling in 1480 BC by becoming Egypt’s first female pharaoh. Throughout her 22-year reign as king, she cross-dressed as a male, wearing a fake beard, a traditional headdress (nemes) with cobra, and a short kilt like her male predecessors.

While controversial as a female pharaoh, and all but erased by her successors, Hatshepsut’s place in history was secured as the only female interred in the Valley of Kings.

Nearby, the Valley of the Queens is only 2 km away by club cart conveyance,

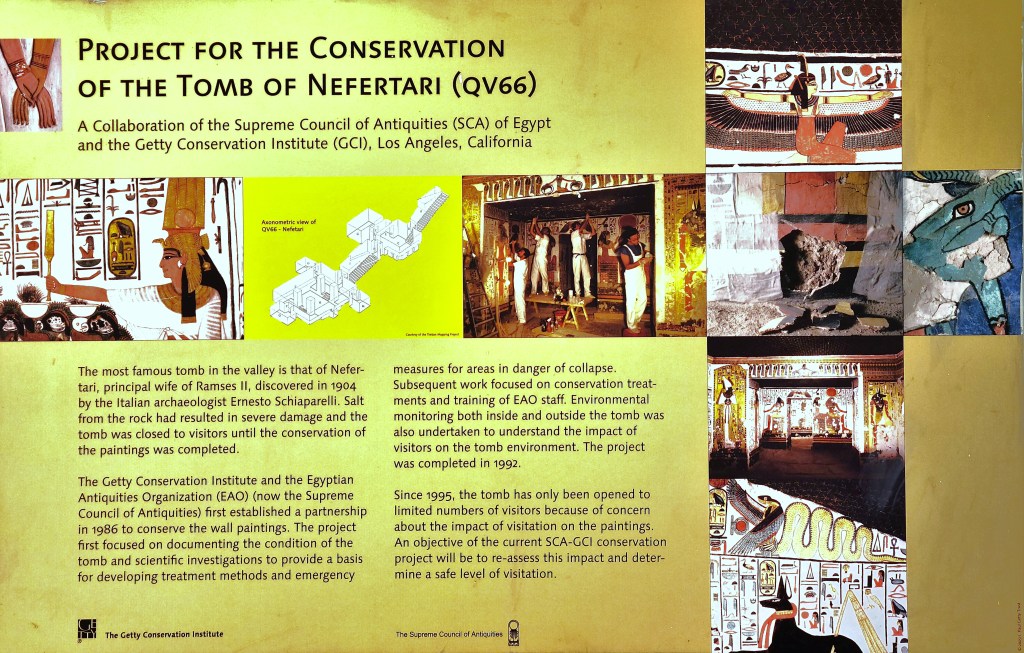

where the shining star of the valley is Nefertari’s tomb.

Officials require a special admission ticket–that only allows 10 visitors at a time to roam through the chambers for only 10 minutes–upon theorizing that reduced traffic likely reduces environmental impact.

Nefertari was the first of Ramses’ II Great Royal Wives (6 in total). In fact, he was so smitten by Nefertari’s beauty, that he built her the grandest tomb on the block, and shared his glory side-by-side at Abu Simbal.

Besides her good looks, Nefertari earned her place at the palace table as the king’s court communicator. She was a writer, a strategist, and a skilled diplomat in support of her husband.

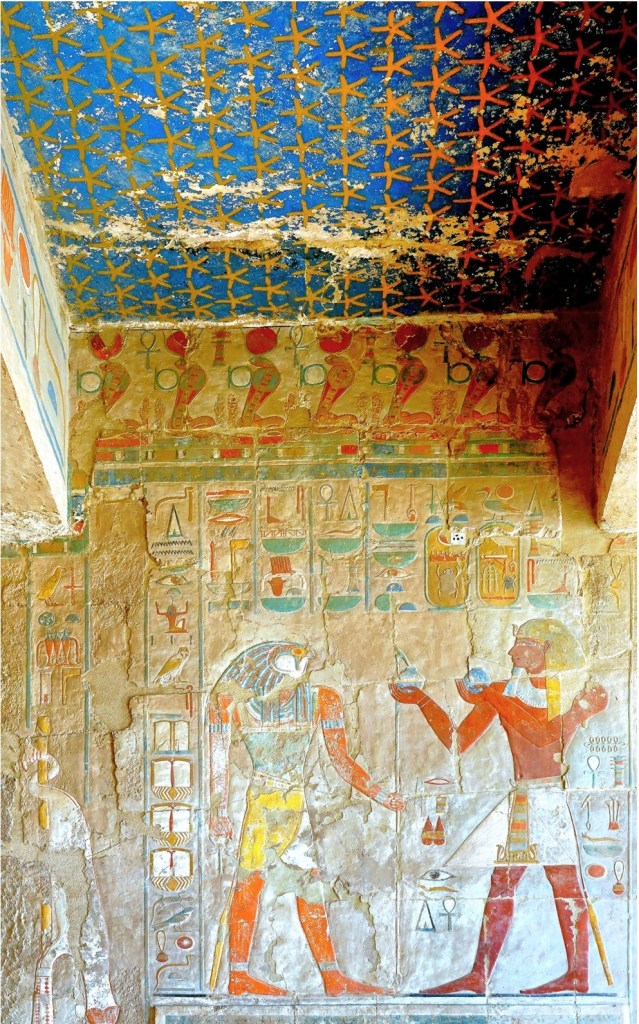

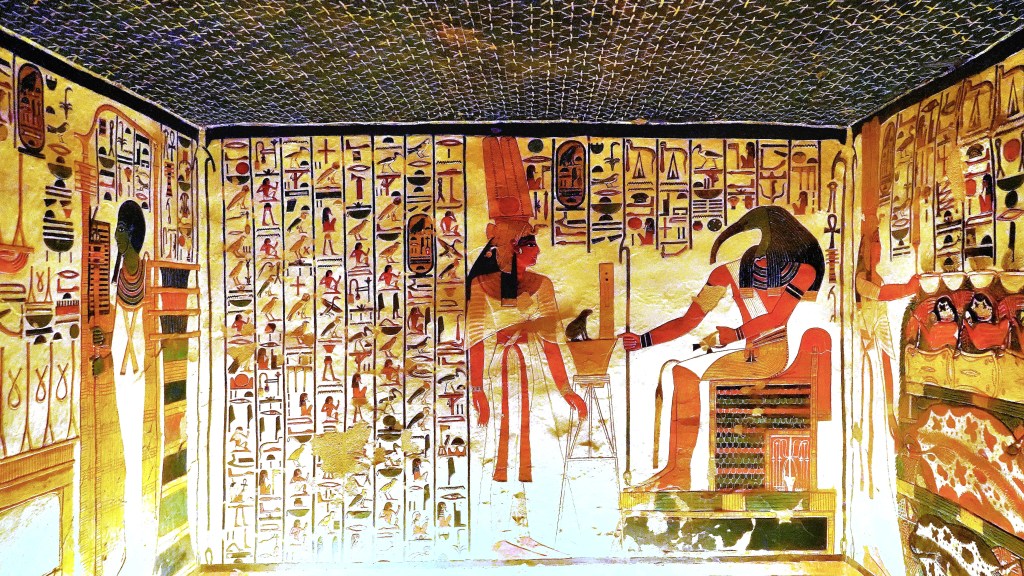

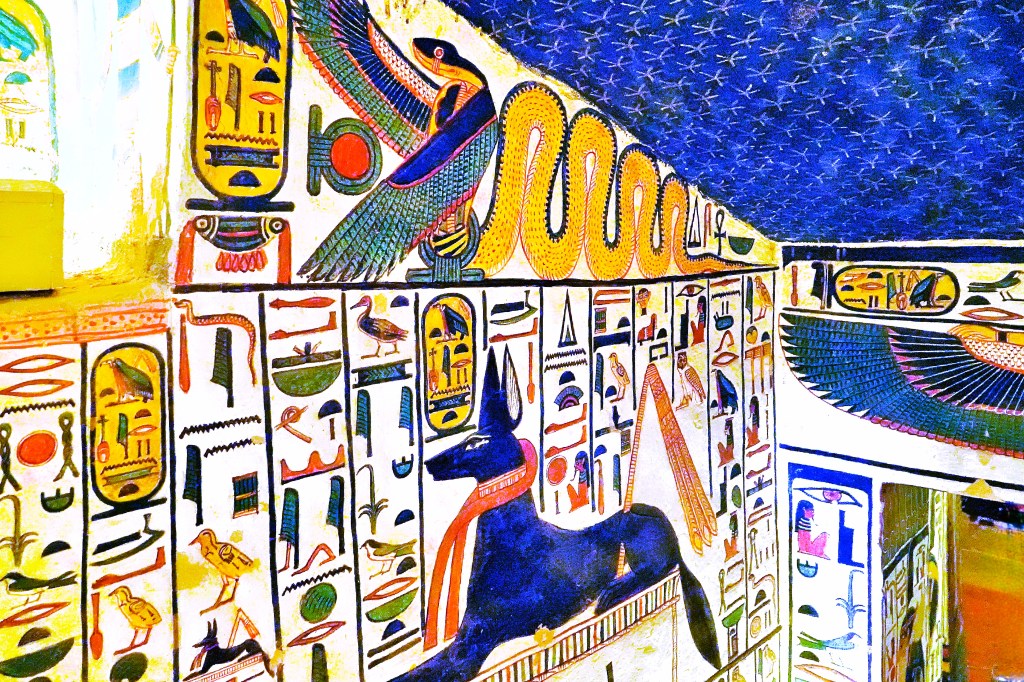

A long tunnel empties into an antechamber…

followed by a second staircase,

that leads to a burial chamber…

supported by elaborately painted columns,

with finely decorated funerary rooms at the wings,

featuring the sacred bull and seven celestial cows, who collectively represent the Goddess Hathor.

Given today’s global issues of gender identity, glass ceiling theory, propaganda, and branding, it might be wise to take a papyrus out of ancient Egypt’s playbook for the benefit of clarity.