Phnom Penh and the Khmer Republic fell to the Khmer Rouge on April 17, 1975.

For the Communists, it was Liberation Day and cause for celebration.

While it marked the end of civil war, it was the beginning of one of history’s darkest chapters. Almost immediately, the Khmer Rouge ordered the exodus of the city’s 2 million inhabitants.

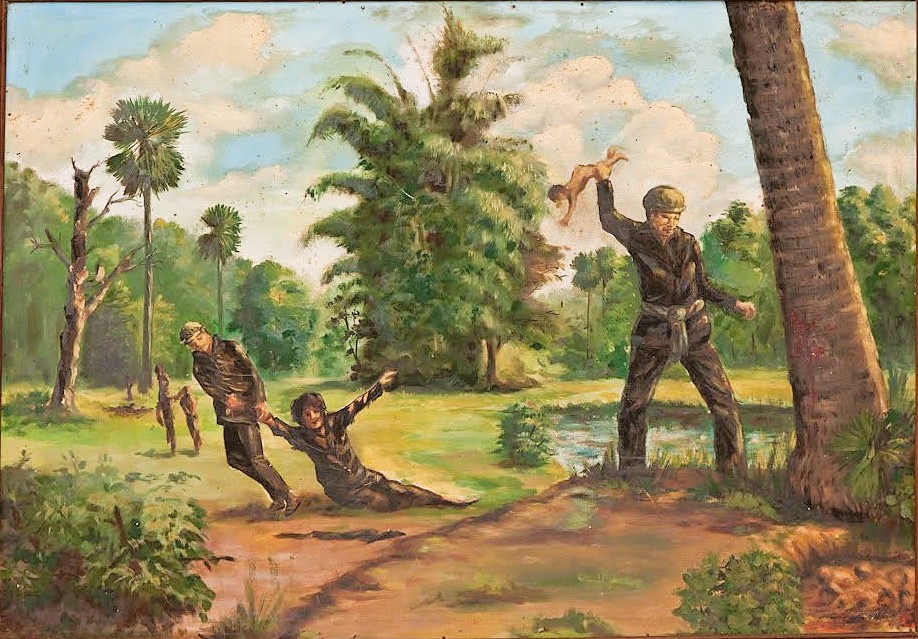

Khmer Rouge strongman, Pol Pot declared 1975 “Year Zero,” in his quest to build a classless agrarian utopia patterned after Maoist China, but it also marked the start of a genocide that would devastate the country, claiming over 25% of the population through forced labor, starvation and slaughter.

It started with a civil servant purge that eliminated tens of thousands of military loyalists, local police, and anyone associated with the previous government. Additional targets included academics, professionals, and “impure” ethnic minorities.

To facilitate the Khmer Rouge agenda, an education campus in Phnom Penh that housed Tuol Svay Prey High School and Tuol Sleng Primary School was commandeered and codenamed “S-21”–the nerve center of the Khmer Rouge secret police.

The survivors remember that day as the day when hope turned to horror, changing their lives forever.

For Vann Nath (tall man in the middle), the unexpected journey to Tuol Sleng began with his arrest in 1978 while working in a rice field. Before 1975, he led a normal life as a commercial artist in Battambang. The Khmer Rouge first detained him at Wat Kandal–a temple turned detention center– and accused him of violating the regime’s moral code before moving him to S-21.

Detainees arrived in handcuffs and were immediately photographed. Today, their images hang on bulletin boards as a numbing reminder of their journey into hell.

Following intake and registration, they were showered.

High-ranking cadres were imprisoned and interrogated in larger cells,

while the masses were confined to bricked-in cubbies the size of shower stalls, with ammunition boxes for toilets.

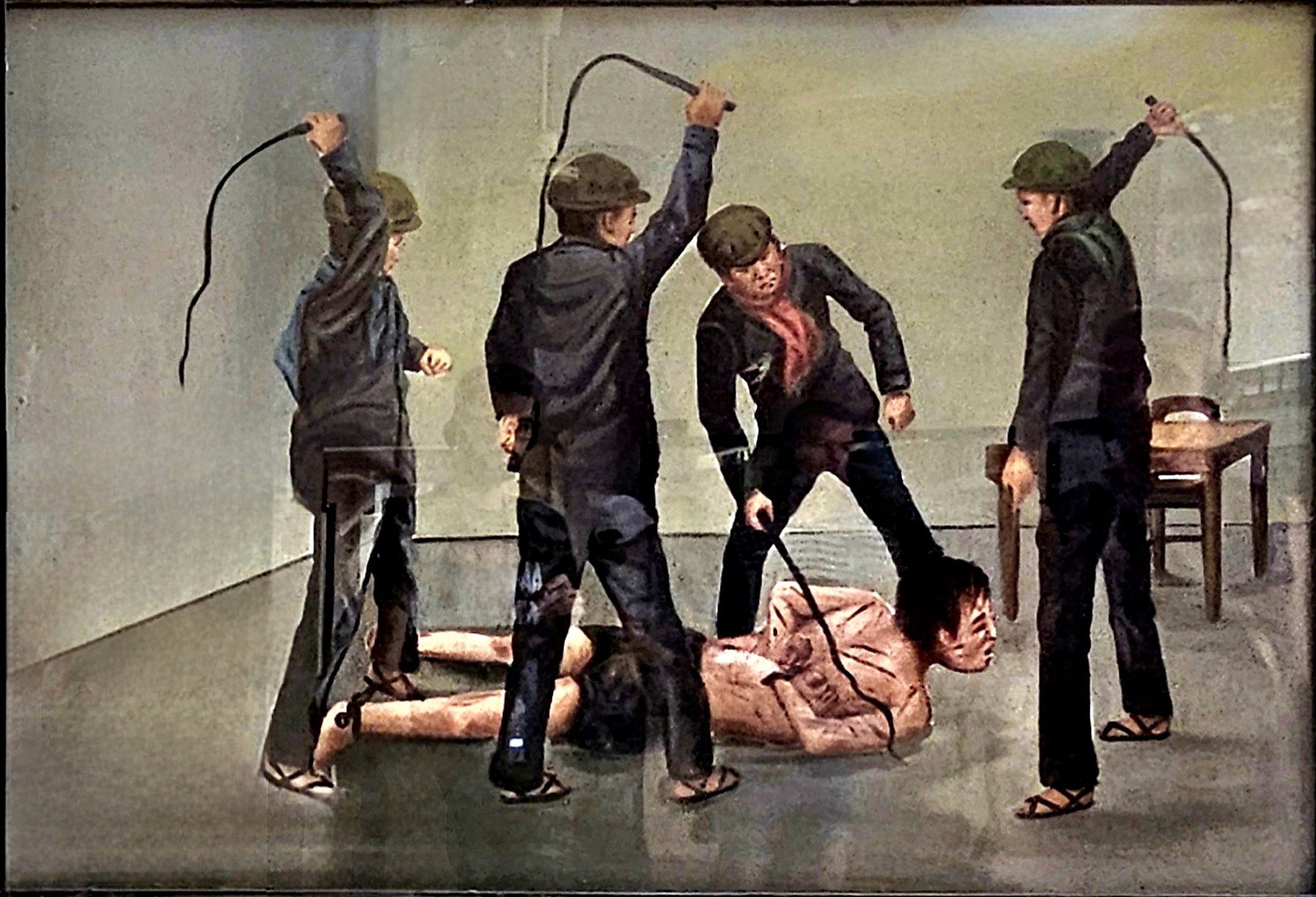

Of course, Vann was interrogated…

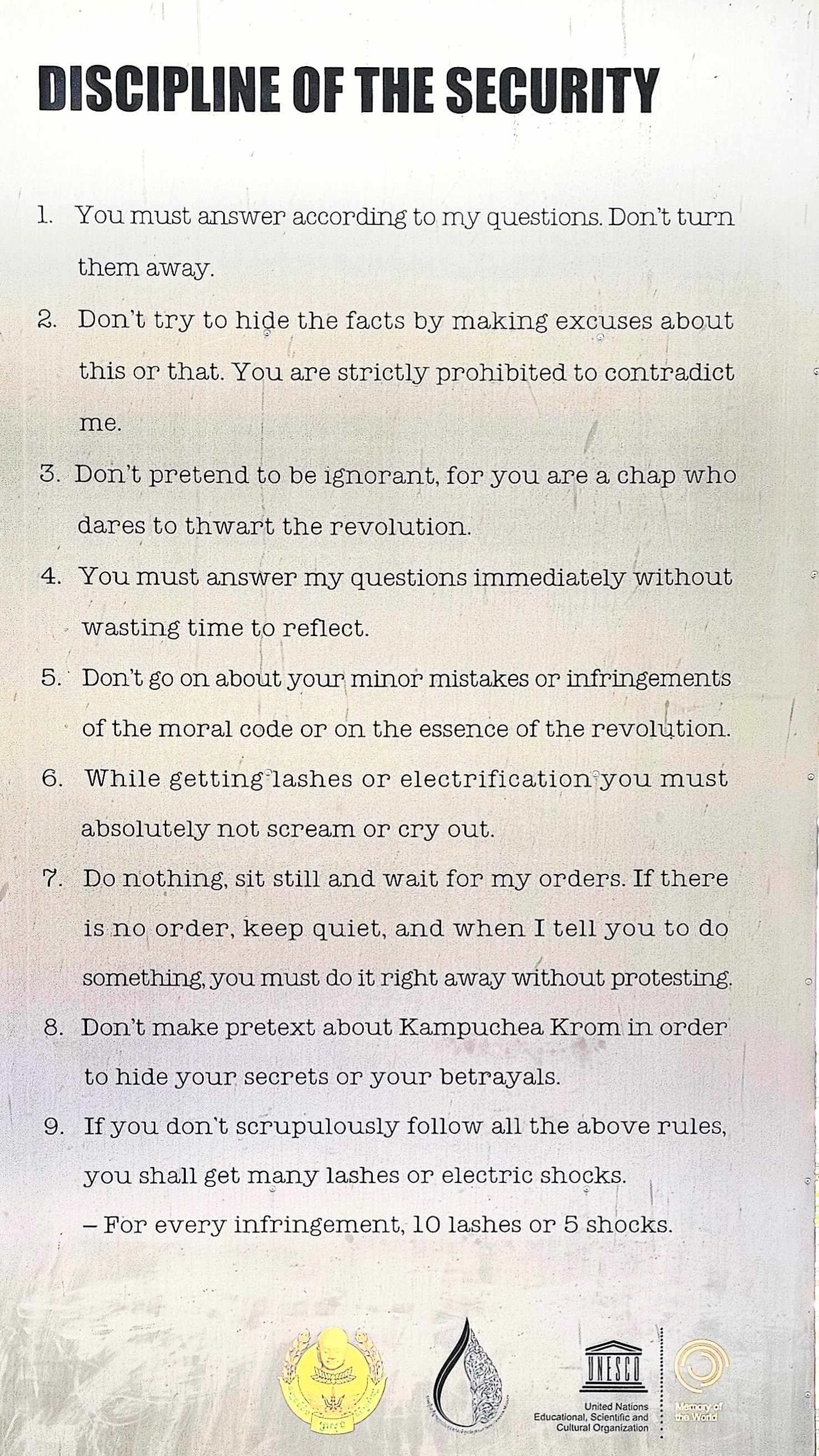

and tortured to extract a confession,

according to a strict code of conduct.

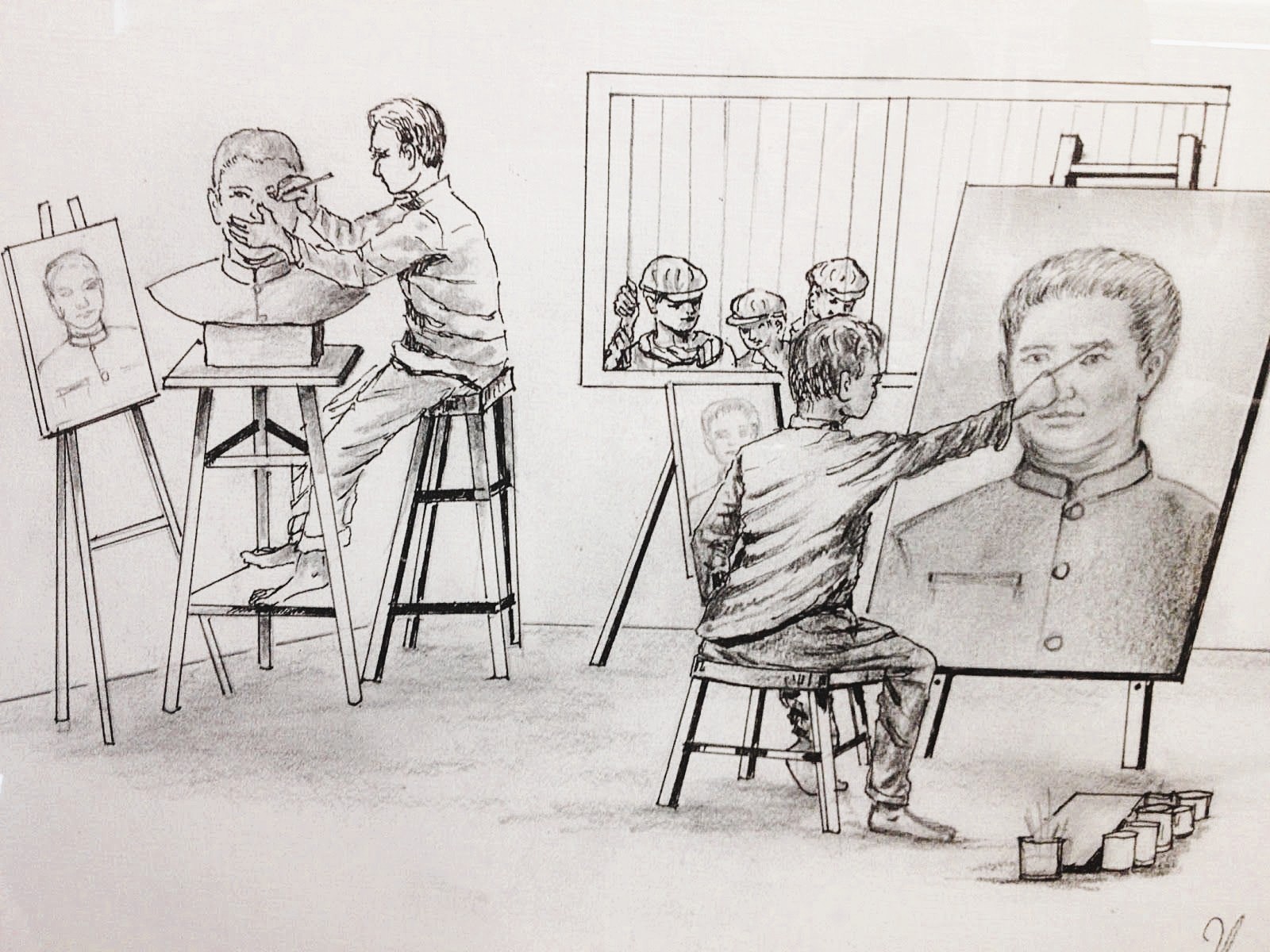

Archives from S-21 reveal that initially, Vann was to be executed, but the commandant spared him in exchange for the portraits he later painted of their supreme leader, Pol Pot.

Vann was among the handful of prisoners who narrowly escaped death by virtue of their special skills and usefulness to the regime.

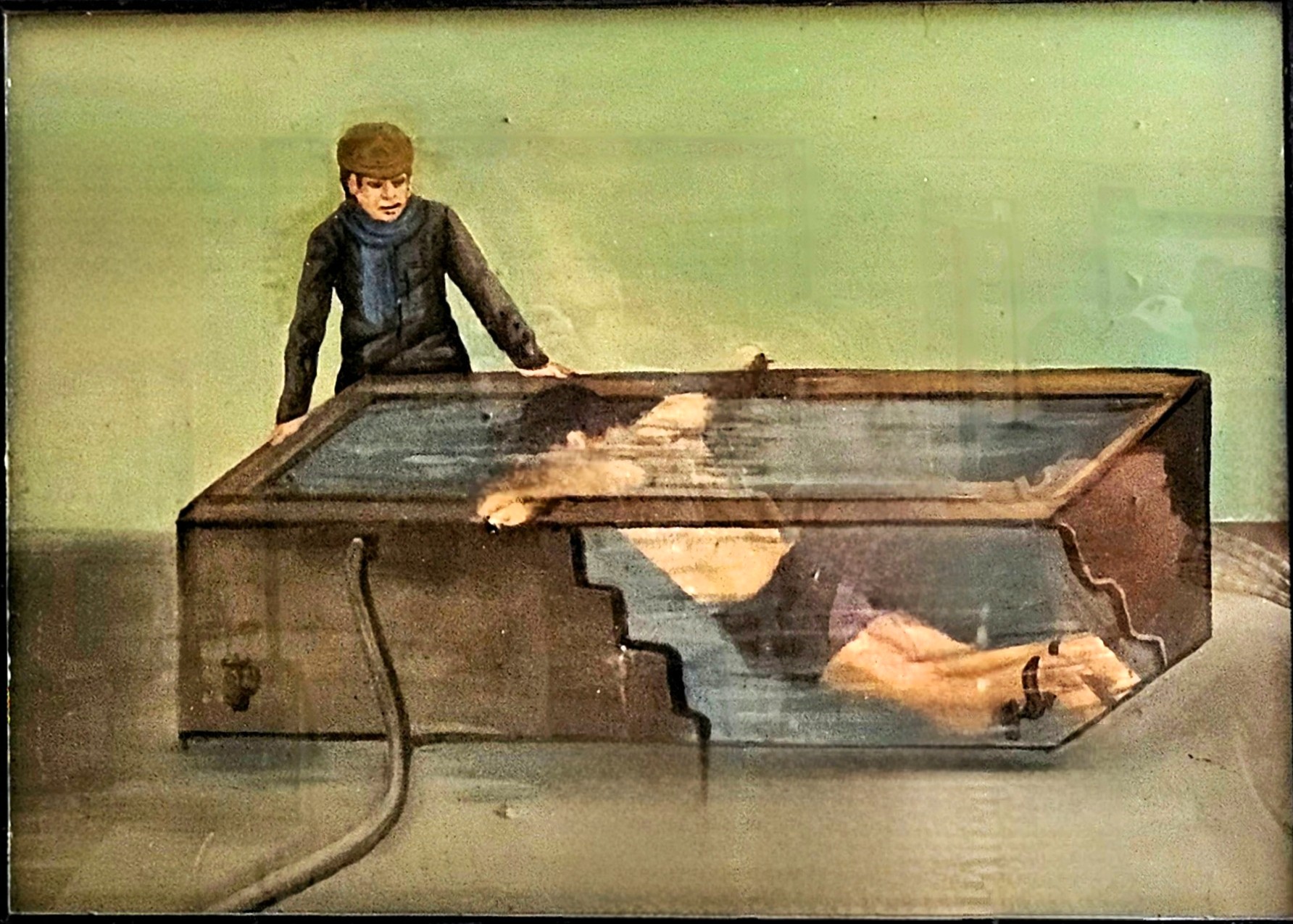

Vann’s first-person account of his misfortune was interpreted years later after his release through a series of colorful graphic depictions–on permanent display throughout the museum–that ironically brings life to the drab surroundings of prison buildings.

These vibrant illustrations vividly capture the stark contrast between the bleak memories of confinement and the essence of freedom, allowing us to connect emotionally with Vann’s experiences.

The cracked walls reflect the forgotten whispers of hope and despair, transforming the narrative into an immersive journey that transcends time and pain.

The art not only serves as a commentary on the injustices faced but also inspires conversations about redemption, resilience, and the profound impact of creativity in the face of adversity.

Chum Mey is another survivor who’s grateful for his mechanical skills. By fixing the typewriters used to record the forced confessions of fellow prisoners, Chum Mey managed to escape a death sentence, but not the torture. He sits at the edge of the museum courtyard, eager to recount his story in horrific detail. “I come every day to tell the world the truth about the Tuol Sleng prison… so that none of these crimes are ever repeated anywhere in the world.”

Our group was also moved by our off-site exchange with Norng Chan Phal, who delivered his oral history through an interpreter. He was 9-years old in 1978, when his world was turned upside down. His father was arrested and executed at Tuol Sleng. Months later, the Khmer Rouge returned for the rest of his family. He recalled his mother’s torture and disappearance, and how he and his brother hid under piles of dirty laundry to escape retreating guards after S-21 was liberated.

Even now, the burden of remembering brings on sudden sadness.

All three survivors later testified against senior leadership before the UN-backed Khmer Rouge genocide tribunal, which led to their convictions.

Tuol Sleng was liberated by the Vietnamese Army in January 1979, and reopened the following year as a museum.

Cambodia’s willingness to confront its past is only one part of the healing process. Youk Chhang, director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) states, “Post-conflict nations must redefine themselves and actively commit to a future without violence, atrocity crimes and genocide.”

I visited in 2023 — such a powerful place. The audioguide really deepens the experience, both by isolating you and intensifying what you take in. Thank you for bringing those memories back!

LikeLike

They are difficult memories, indeed. History only tells part of the story.

LikeLike